Citizenship, Migration and Climate Change in Contemporary India

Where is your desh, chotu?[1]

B T Road.

Calcutta Panchway, Book Illustration, “Narrative of a journey through the Upper Provinces of India from Calcutta to Bombay 1824-25. (Edited by Amelia Heber), 1828. British Library Collection / Public Domain.

Under the prevailing definition, refugees are those expelled from their homestead due to war, religious persecution, political upheaval or other such violence. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), for instance, only counts those displaced due to armed conflicts as refugees to this day. But is this an adequate or sufficient understanding in today’s world where, thanks to the operations of neoliberal global capital, people in the poorer parts of the world are expelled from their livelihoods, homes and biospheres on a regular basis, as illustrated by the urban sociologist and geographer Saskia Sassen in her book, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy (2014)[2]? Strangely, this issue has not come to the fore even in the wake of India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019. The ongoing debate – furious, spontaneous and countrywide as it is – remains tagged around the question of which communities (in neighbouring countries) are to be considered legitimate refugees for reasons of religious persecution.

The text of the Act, admittedly, makes no direct mention of religious persecution. But the Statement of Objects and Reasons (SoR) in the Bill that preceded the Act does, as does the Home Minister’s speeches in both Houses of Parliament. Who are the migrants who can expect to get immunity by dint of CAA? There are three different requirements. The first is the requirement of nationality; which means that one must have come from Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Bangladesh. The second requirement is that of religion, meaning one must belong to the Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Christian or Parsi communities. Notably missing in the list are the Muslims. The third is the requirement of time. One must have come to India on or before 31 December, 2014. The Minister has explained that in the three neighbouring countries – Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Afghanistan – the Muslim community constitutes an overwhelming majority with Islam as their official religion. These countries also have a history of ostracization of minority communities. Hence, he persuaded, it was only logical to leave out the Muslim community from amongst those who can legitimately be recognized as refugees on religious grounds from those countries. (In a later section of this paper – Citizenship Documented: the unending tango of Aadhaar, CAA and NRC – we discuss in detail the several lacunas and politics of the Act).

At the time of partition, East Pakistan was left with a substantial presence of Hindus, most of whom crossed the border in the following decades. What the Hindu upper-caste babus had practiced with the Bengali Muslim peasants and Dalits in undivided Bengal was no better than a colonial version of apartheid. In my view, this was the primary reason why India was partitioned in the east in 1947; over and above other factors such as the divide and rule policies of the Raj or the slow rise of a modern variant of Islamic fundamentalism in the eastern parts of the region.. Once having crossed the border – and by then bereft of all stakes in land and property – the Hindu babus could afford to be true-blue seculars, at times even revolutionary in their zeal. Meanwhile, the flow of people coming into India continued unabated. It can safely be stated that by the 1970s, the upper caste Hindus, by and large, had come over to India to start life anew. Today, those left behind in Bangladesh are mostly people from OBC categories and the Dalits. No wonder the babus, in the course of time, forgot the plight of those who stayed back. As a matter of fact, any talk of the condition of Hindus in Bangladesh is now considered to be adding grist to the communal machine. Admittedly, independent Bangladesh hasn’t witnessed anything as spectacular as a Godhra. But incidents of everyday harassment of Hindu minorities – especially those living in the villages – continue, which are on economic grounds as much as religious ones(more often, the two together), accounting for the reason why border-crossing has not come to an end even today.[3]

Pakistan presents a picture in contrast. The unprecedented violence that followed the partition led to a near total transfer of population in the two parts of Punjab – the Sikhs and Hindus from West Punjab into India and Muslims from East Punjab into what was then West Pakistan. Consequently, the Hindus who stayed back in West Pakistan were far less in number compared to East Pakistan. By all indications, the Hindus in Pakistan are now a fairly stable community and reportedly going up in number.[4] In Afghanistan, after the collapse of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, the few thousand Hindus who lived there mostly left. The number today is no more than a thousand, mostly in and around Kabul. The reason for including Pakistan and Afghanistan in the CAA is only ostensibly for providing shelter to the fleeing non-Muslim Indians; more significantly, I suspect, it is to prevent Muslims from coming to India on grounds of security, always a good bogey for the state.

Modernity and the Borders of Nations

Book Cover of ‘Toward Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,’ 1795. (Wikimedia Commons).

Nationhood, by definition, preserves the right to decide who is illegal and who is not. Immanuel Kant’s influential essay, Toward Perpetual Peace (1795), draws a blueprint for nascent European nation-states in the context of the emerging imperial order. The rights of foreigners that he prescribed went nothing beyond the right not to be treated with hostility as long as they themselves were not hostile, although they could be turned away any time as long as their return to the country of origin wouldn’t certainly cost their lives. Clearly, hospitality here is not on demand but on offer.[5]

The essay is a kind of thought experiment but on well worked-out practical grounds. As commentators have pointed out, it is a direct response to the historical conditions prevailing at the end of the reign of terror in the French Revolution, and aims to steer Europe out of uncertainty and national hostilities. What is interesting to note is that in the process of presenting a plausible formula, it also lays the foundations of the imperial geopolitical order to come. In fact, it may be suggested that Kant’s political writings (as well as his works on ethics) can be read as a kind of blueprint of future liberal rule. A permanent army posted at the border as part of an active peace apparatus, vigilant police inside the country and a self-monitoring subject-citizen whose art of independent thinking does not only not defy but, as a matter of fact, is hemmed into the art of obedience: this tripartite arrangement is Kant’s prescribed path for balance and progress in Europe.

‘Perpetual Peace’ is a project and, as a project, it is easier for readers to see its alignment with the project of enlightenment as such. Peter Fitzpatrick, in the essay “Desperate Vacuum,” throws light on that perilous but utterly necessary space of liberal legality between the project of enlightenment — with its incurable energy in discovering the general (universal) in the particular (Europe) — and the recalcitrant, intractable nature outside the operative sway of this project.[6] In ‘Perpetual Peace,’ Kant is talking of a certain pact between republican nations. So this then becomes the inside/universal/Europe. Outside would be what lies outside this pact: i) areas of Europe and other parts of the civilized world where the republican order will take time to come about (hence, a temporal project) and ii) the vastness that lies outside the civilized world held, tenuously, between the temporal and the anthropological and for which the outcomes would ever be uncertain. The border then becomes an issue of a certain kind of republican order into which the larger part of humanity needs to be trained and cultivated and which, in keeping with the uncertainties of the trajectories of the temporal/anthropological mentioned above, will always remain an unfinished project. Carl Schmitt was shrewd enough to understand that a combination of three processes – appropriation, distribution, and production – always set up the conditions for modern legal, economic, and social order. So the emergence of borders in modern Europe cannot be dissociated, as Schmitt points out, from the political arrangements that characterized the imperial geographic distribution.[7]

In a way, this has remained the order for international relations. Getting back to the issue of the CAA, the British media, on its part, has been expectedly critical of the Act, forgetting Britain’s recent shabby record with accommodating refugees from war-torn Syria. In February of this year (2020), the prestigious Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies devoted a whole issue trying to dismantle the myth that with the post-World War II shift in admissions criteria from race and national origin to skill and family ties, the Global North has been following a non-discriminatory migration policy. Article after article in the issue laboured the point that European immigration policy is determined by an intersection of several factors that increasingly includes religion. The dominant sentiment that guides migration thinking still remains:, ‘we are who we are by virtue of who we are not.’[8] Arguably, it is the same sentiment that has colored the CAA 2019.

The earliest expression of capital-border alignment is the enclosure of common land. This is also, as Rousseau approvingly points out, the first step to civil society.[9] The legitimacy of the border of nation-states comes from an understanding of the state as an administrative machine; hence the priority on delimitation. The border as we know it today is predominantly a modern affair, marking a complex relationship between capital and the state. The flow of capital is constitutive in understanding the border. This involves the circulation of human bodies which in turn is inalienable from the commodity of labour power to be transacted as goods in markets.[10] Thus the modern border is an amalgam of the state as administrative apparatus, the flow of capital and human bodies, and ultimately the buying and selling of labour power. The arrival of new capital has finally done away with the Westphalian dream of neatly demarcated stable nation-states. Even as this is so, at the other end of the same spectrum the more unpredictable the movements of heterogeneous labour become, the more the border takes the shape of an assemblage of power and law, thus attributing the nation-state with new importance.

Balibar observes that to mark out a border is not only to delimit a territory, but also to confer identity to it. The state expects the citizens to internalize what the country’s border stands for culturally, politically, socially, and quite often, religiously. Or, more importantly — looking from the other end of the periscope — they recognize what it absolutely does not stand for.[11] But a border is not merely a running line. A border carries a history of determination depending on the power ratio of the determining nations. Colonized spaces anyway were always crisscrossed by borders demarcating the spatial limits of compromised sovereignties that existed within the domain of the Raj. Because of conjoined history and geography, the borders of postcolonial states have always been fragile, with remnants of unhealed sores. The era of new capital has added fresh spatial disruptions to this unreconciled scenario.

Mode of Transport used during the Partition of India, 1954. (Wikimedia Commons).

A nation-state acquires complete sovereign control of the border by identifying who gets entry and who doesn’t. Inclusion and exclusion are part of a single continuum where today’s included may become tomorrow’s excluded and vice-versa; a power matrix overdetermined by economic processes. As part of the labour market, humans are here calculated as units of finished products and not as processes of creation. “Just as classical political economy removed from the historical horizon of capitalism the “original sin” and violence of primitive accumulation, naturalizing the “laws” of capitalist accumulation,” write Mezzadra and Neilson, following Marx, “so modern cartography congealed the ontological moment of the fabrication of the world, constructing its epistemology on the idea of a natural proportion and measure of the world, an abstracted fabrica mundi to be projected onto maps.”[12] This is why borders have an underbelly that narrates unspoken histories, mostly of violence and personal tragedies.

As should be clear from the above discussion, borders are by definition polysemic in nature and hence do not carry the same meaning for everyone. People experience them differently, depending on their own locations in the cultural and political space of the nation. So the ‘world configuring’ function of the border that Balibar points out is, on a subjective or community level, necessarily split. A border is part of a larger grid and the country’s external border is necessarily linked with the numerous internal borders operating in the nation. A border, even if hypothetical or a fiction, is no less real. In the neoliberal era, the more the transnational traffic of people or capital intensifies, the more states tend to use their borders and international controls as instruments of discrimination and triage. Yet it is important, says Balibar, for the state to preserve the symbolic sources of borders for their popular legitimacy[13]. This is the main source of contradiction in the regime of borders.

Migration and Postcolonial Neoliberalism

With the coming to dominance of neoliberal capital from the late 1970s onward, the number of those forcibly expelled from their homestead and floating around the world due to ecological degradation and structural ‘adjustment’ of the economy has by all accounts exceeded the population made homeless by war, religious persecution and other kinds of violence[14]. This is not to suggest that displacements related to violent confrontations are by any means going down in number. Thanks to a string of never-ending wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East that began at the turn of the century – not to speak of communal and ethnic flare-ups across the world – the number of those fleeing from violence and persecution is actually massive. The US is now in the process of withdrawing from that region but the internecine strife they are leaving behind shows no sign of abetting. But even after taking all these sources of conflict into account, by all indications displacement due to climate change as well as structural changes of the global South’s economy (initiated by the IMF, World Bank and other international lending organizations) have already started outnumbering all other categories of migration put together; so massive and extensive has been the impact of a worsening ecology combined with the neoliberal onslaught on the poor. (Here it is important to remember that by postcolonial neoliberalism, we mean the weaving together of neoliberal economy and culture with those of postcolonialism towards the co-constituent formation of market/economy and nation/culture. This ensemble changes the character of neoliberalism as it is known in the West and also of postcolonialism. It is a hybrid new creature whose reality is undeniable though it remains to be properly defined.)

The only surviving page of the first draft of the Communist Manifesto in Karl Marx’s handwriting, 1847. (Wikimedia Commons).

It is now common knowledge that disaster is part and parcel of capitalism. Its relentless quest for profit, as Marx and Engels had observed in the Communist Manifesto, impoverishes the vast majority of the human population, puts all wealth into the hands of the few, plunders the earth and toxifies the environment. Neoliberal capital only intensifies this process. Super cyclones and increased salinity of water is directly related to global warming. Toxification of the environment leads to the frequency of life-threatening bacterial and viral outbreaks, of the kind the world is currently witnessing. And every such natural or biological disaster causes fresh outbreaks of global migration of the poor. While this is true, capitalism for its part creates new avenues for profit out of disasters. In this paper, we discuss two kinds of disaster migration in contemporary times: first, climate migration and second, the ongoing COVID-19 migration from the cities of India to the villages the migrant workers come from.

At the very start, however, it is better if we remember that neatly isolating a social phenomenon and calling it ‘climate migration’ is much more difficult than we often imagine it to be. Unless it happens to be a case of a big-time storm uprooting houses in thousands or an equally major flood, people do not leave their homes exclusively for ecological reasons. It is also not an overnight affair. Ecological damage happens over a period of time and remains imperceptible at the beginning. Quite often, by the time we start noticing any marked change, the damage has gone far too deep for redressal. More importantly, it is only in the combination of other factors such as poverty, social and religious marginality, etc. that ecological or climate change becomes an effective enough trigger for people to leave their homestead and seek refuge in a neighbouring land. This is the main reason why climate migration is rarely treated by international organizations as a category on its own.

Expulsion, says Saskia Sassen, is the reality of global capitalism’s pathologies manifested in the form of the tattered social fabric and thick realities of poverty and inequality. It is now clear that the predatory modes of neoliberal capital are the primary cause of ecological devastations. While systemic expulsion makes the oppressed a huge but scattered multitude, the oppressor is increasingly a complex and elusive network with no obvious centre.[15] The rise of global finance means securitizing through endless means of surveillance and a corresponding retreat from the Keynesian model of mass investment in infrastructure and mass employment. As Keynesianism gave way to a global era of privatization and open borders, people were pushed out of jobs and habitats. They are the new refugees of an era framed by neoliberalism – an unrecognized but mammoth reality that is only going to expand in the coming days.

Pyramid of the Capitalist System, Industrial Workers of the World Poster, 1911. (Wikimedia Commons).

With capital moving deeper into the recesses of the economy worldwide, the contradictory and uneven character of capitalist development becomes even clearer. Institutions like the World Bank, of course, try to depoliticize the ‘project of development’ that involves dispossession, making it look natural and legitimate.[16] The only Archimedean point that capital would agree about itself is the tale of its universality. But in terms of development, something greatly significant occurred as capital turned its focus from manufacture to real estate and the capitalization of natural resources (the vast rise of the tourism industry is one example). This, along with the rapid rise of labour-saving technology, meant that capital prioritized expropriation of the natural resources of the poor (primarily, land) over the exploitation of their labour. This is, however, only part of the picture of the erstwhile colonies. As labour-intensive factories started to close down and menfolk lost their jobs, the women – mothers, sisters, and wives – were typically asked to bear a good part of the weight of urban structural adjustments.[17]

The free fall of capitalist profit in the West from the late-1960s to the first half of the 1970s caused a global economic crisis. This offered the ruling class the legitimacy needed to start dismantling the edifice of the welfare state. Since then, the onward march of global capital has been clearly in the neoliberal direction. With neoliberalism, capitalism entered a more advanced phase, reinventing far-reaching mechanisms for primitive accumulation. What has emerged since the 1980s is an immensely sophisticated algorithm of finance, an interconnected geography of extraction,[18] and a rapid and homogeneous technology of city-making, creating overnight cities out of what only yesterday was vast stretches of rural habitation and farming, to cite a few examples. Added to this is the regular dumping of toxic waste in vast stretches of land. All of these have led to a huge concentration of wealth and the equally vast pauperization of the already underprivileged. The new emphasis on primitive accumulation in the era of advanced capitalism has been characterized as ‘accumulation by dispossession.’[19].

Nationalist developmental thrust and expanded reproduction that marked the economic policy of the welfare era has now been replaced by an economic policy that advocates for a free market to function without significant state intervention. Mike Davis, citing the advocate of neoliberal economic order Hernando de Soto (known for his ‘boot-strap’ model of development), has explained how this works out for the poor parts of the world: “Get the state (and formal labor unions) out of the way, add microcredit for micro-entrepreneurs and land tiling, then market will take its way.”[20] He observes: “Altogether, the global informal working class (overlapping with, but non-identical to, the slum population) is about one billion strong, making it the fastest growing and most unprecedented social class on earth.”[21] Davis’ comment on urban poverty in the era of new capital is memorably cryptic: “Slums, however deadly and insecure,” he says, “have a brilliant future.”[22] Kalyan Sanyal, in his influential 2007 book, Rethinking Capitalist Development: Primitive Accumulation, Governmentality and Post-Colonial Capitalism has also demonstrated how within the capitalist circuit of production, distribution, and circulation, the entrepreneurs of the informal sector have created an economy — the need economy as he calls it —outside the ambit of accumulation for mere survival. In a conversation between Sanyal and political theorist Partha Chatterjee, the process was explained thus:

“ Sanyal: …The distinctiveness of the present moment of globalization is the realization that a subeconomy must be created for the excluded. If one deconstructs the discourse of development, this is what one gets, and that’s what I have tried to show.

Chatterjee: So you are saying that there is a split in the postcolonial capitalist formation in which there is capital’s own space and another space that is a subeconomy . . .

Sanyal: Yes. I am calling the first the accumulation economy, which runs according to the logic of capital, in which the dynamic force is technical progress and accumulation. The subeconomy I am calling the need economy, which runs on a different logic — the logic of need or the minimum conditions of subsistence. These two economies lie next to each other. In one, there will be growth; in the other, there will be the distribution of microcredit, promotion of self- employment, creation of self- help groups. The discourse of development now speaks of this new dual economy. Development will, on the one hand, foster growth in the accumulation economy and, on the other, rehabilitate the excluded in the need economy. Together, the accumulation economy of capital will be legitimized, made acceptable.”[23]

To consider the toilers in the informal sector “ragged-trousered capitalists”, observes Davis, is a primary ‘epistemological fallacy’ of contemporary economics, which mistakes the daily struggle for ‘sub-subsistence’ for ‘micro-accumulation’.[24] As a matter of fact, the boom of the informal sector, as Partha Chatterjee argues in his recent book, I am the People: Reflections on Popular Sovereignty Today,[25] is nothing but ‘passive proletarianization,’ which directly relates to the liberalization of the economy. In the Nehruvian era, the Indian state asked for common sacrifice for the greater good of ‘the nation’. There was an attempt — or at least a hope in the early decades of independence — to bring the poor and marginalized into the economic mainstream, thus absorbing the surplus population of the agrarian sector into industrial jobs. That is not even an option any more. Rather, when it comes to agriculture and issues related to land, the state provides the aegis to private capital in the promotion of real estate. This has meant a corresponding loss of the state’s moral persuasiveness. It is a fair guess that the state tries to fill this lack up through populist rhetoric.

In the recent past, we have often been reminded that India’s vast young population will reap rich dividends in the near future. Like many other pronouncements of the state, this too is superficial. The demographic dividend will give good results only if proper steps are taken for the promotion of human capital – namely, quality healthcare and education, better job creation and proper training for skills. As per the annual data released by the government of India in October 2019, India spent only 1.28% of its GPD (2017-18) as public expenditure on health.[26] The Government of India spent 3% of its total GDP on education in 2018—19 which, as per the International Institute of Management Development (IIMD), Switzerland, ranks India sixty second in total public expenditure on education per student and measures of the quality of education (pupil-teacher ratio in primary and in secondary education).[27] After 15 years of ‘gender budgeting’, India still has deplorable records in women’s health and education, especially for job-creating skills. When a gender budget was introduced in 2006 as a separate section of the Union budget, 4.8% of total spending was allocated for women-related schemes. This was increased to 5.5% in 2009 but has stagnated ever since.[28]

Migration and the Impact of Climate Change

It was quite a shock to be told by climate scientists that the nature around is changing, that the Himalayan glaciers are melting, that there would come a time when the river Ganges so sacred for millions may not be there anymore. But the harder shock as a social scientist to absorb was the news that the human beings as a collectivity have become a geological agent on this planet. In other words, that the climate is changing has some to do with what we are doing, as a species, as a collectivity…

Human beings are biological agents, we have ecological impacts. But this news is new when geologists and scientists began to say that a new geological period may have begun which they propose to call anthropocene. Holocene has ended, anthropocene has started. It really shook up all my assumptions as a social scientist, because in political thought, in social science you always assume that the geological calendar is completely indifferent to the calendar of capitalism, socialism, feudalism, on which we teach human history in the classroom. …

Their (geologists) sense of urgency with regard to the impossible that is bringing the geological sublime within the realm of affect only point to the political and intellectual challenge to the current crisis. Out of this may very well emerge a new kind of politics. Such politics has to take into account not only the political and sociological but the biological and geological as well. This politics will supplement climate change politics based on the more short run politics of market principles, political negotiations, and technological fixes.

Dipesh Chakrabarty (‘Breaking the Wall of Two Cultures’)[29]

As mentioned early in the discussion, in today’s world, the question of migration loses meaning without including the impact of climate change. Down-to-Earth (DTE), an ecology journal, reports that in 2018, India had the highest number of people (2.678 million) displaced by turbulent weather conditions and extreme climate; in 2019, the number was slightly higher, roughly 2.7 million. By 2050, experts estimate that around 200 million people will be forced to leave home of which, it can be safely stated, the number of South Asians will be around 40 million. DTE notes: “In 2018, of the total new 28 million internally displaced people in 148 countries, 61 per cent were due to disasters. In comparison, 39 per cent were due to conflict and violence. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), storms displaced 9.3 million people and floods 5.4 million. Similarly, more countries reported displacement due to disaster than conflict and violence: 144 for disaster and 55 for conflict and violence. According to the UN, disasters and geophysical hazards have an average of 3.1 million displacements per year since 2008.”[30] Norman Myers, a specialist in this field, is of the opinion that environmental refugees will rank as one of the foremost humanitarian crises of our times.[31]

Citing from the Fourth Assessment Report (April 2007) of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC), Elizabeth Ferris points out how anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations bring significant changes in many physical and biological systems.[32] Climate change effects may be sudden and violent, like floods, hurricanes and other natural disasters. They can also occur over a long period of time – like desertification, salinization of soil, the rise of water level, etc. The two, however, are related. To give one example, desertification or sustained lack of rain may make bushes more prone to catching fires. In addition to this, armed conflicts lead to climate destruction, which itself is used as a tool of war.[33] What is most worrying is that with sustained ecological damage, as Ferris underscores, there is a faster rise in hydrometeorological events. To illustrate her point, she presents two graphs that the UN’s International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction has brought out. They are reproduced below: [34]

The question is: is climate change directly related to migration? Let us point out here that the two different kinds of climate change open up two different scenarios. Natural disasters like floods or cyclones trigger immediate movement to safety. At times the evacuees return home within a short period, and at times they set off to some other place if their original habitat is beyond redemption. But slow-onset disaster due to environmental erosion – like the rise of sea levels and related increases in the salinity of coastal soil, toxification, sustained drought or persistent crop failure – is a different phenomenon in terms of migration behaviour. Everyday changes and episodic changes in ecology add up to bring about long-term climate change. The decision to migrate is a complex of different factors, of which climate change is an important driver among others, including poverty and, at times, socio-political reasons. In other words, there is no mono-causality available. Also important to remember is that economic and ecological marginalization happen together. To cite a few examples, an undermined ecosystem will bring down the fertility of the soil and the availability of adequate water, leading to crop failure. Similarly, a persistent increase in extreme weather events or salinity of coastal soil due to rising sea-level will make agriculture unviable.[35] If environmental degradation makes human subsistence difficult, people will at some point move out, but when and how this may happen depends on other surrounding causes. Understandably, it is not always clear whether the decision to migrate is voluntary or forced. Mostly it is a fuzzy zone, underscoring the need for a new mode of classification that institutional agencies and policy bodies depend on.

The question is: is climate change directly related to migration? Let us point out here that the two different kinds of climate change open up two different scenarios. Natural disasters like floods or cyclones trigger immediate movement to safety. At times the evacuees return home within a short period, and at times they set off to some other place if their original habitat is beyond redemption. But slow-onset disaster due to environmental erosion – like the rise of sea levels and related increases in the salinity of coastal soil, toxification, sustained drought or persistent crop failure – is a different phenomenon in terms of migration behaviour. Everyday changes and episodic changes in ecology add up to bring about long-term climate change. The decision to migrate is a complex of different factors, of which climate change is an important driver among others, including poverty and, at times, socio-political reasons. In other words, there is no mono-causality available. Also important to remember is that economic and ecological marginalization happen together. To cite a few examples, an undermined ecosystem will bring down the fertility of the soil and the availability of adequate water, leading to crop failure. Similarly, a persistent increase in extreme weather events or salinity of coastal soil due to rising sea-level will make agriculture unviable.[35] If environmental degradation makes human subsistence difficult, people will at some point move out, but when and how this may happen depends on other surrounding causes. Understandably, it is not always clear whether the decision to migrate is voluntary or forced. Mostly it is a fuzzy zone, underscoring the need for a new mode of classification that institutional agencies and policy bodies depend on.

Since the international protection regime is predicated on the idea of forced exile, it is not at all certain whether migration due to gradual environmental degeneration will be recognized as valid grounds for legal protection in the near future. As of now, climate change is not within the purview of the law. What has, however, been accepted in the parlance of research and international policy bodies is that climate change is an anthropogenic affair. But this acknowledgement has offered little help in extending the scope of international legal recognition; cross-country migration for climate-related changes remains an issue left at the mercy of receiving states. Since the legal regime goes by the understanding of forced migration, all that matters to policymakers is the prospect of ‘imminent harm’, echoing Kant’s position in the essay ‘Toward Perpetual Peace’ (discussed earlier). It should be clear by now that the poorer parts of the world will experience climate-related changes more sharply than the developed regions. This is due to what has been called ‘the resources-poverty paradox’ – that is, if resources and technology increase adaptive capacity, poverty limits it. It is indeed a tricky situation since in creating better resources and technology, the ecology is often damaged.[36]

Myers (2002) argues that climate refugees from Bangladesh alone might outnumber all current refugees worldwide, estimating the figure at 26 million.[37] Bangladesh is composed largely of low lying land areas, about 80% of which is flood-prone. Citing the Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS)’s estimate, Panda reports that about 17.5 percent of the total land area will be inundated and 11 percent of the population will be displaced by a one-meter rise in the sea level alone. 40% of the total land area and 46% of the total population in Bangladesh are currently in the low elevation coastal zone (LECZ).[38]

A Post of the Bangladesh India Border, (Wikimedia Commons / CC By – SA 4.0).

From a nation-state perspective, India has reasons to be worried about the ecological conditions of Bangladesh. At the same time, it has been argued that India’s Farakka Barrage has put Bangladesh into serious ecological jeopardy. Citing T. N. Chowdhury, Panda points out that the western region of Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to droughts, and that water from the Ganges can help to mitigate the impacts of droughts. Similarly, saline water intrusion is a major problem in the southwestern region of Bangladesh. All this goes to show how ecological problems cannot be assessed, let alone solved, strictly from within the parameters of a particular nation-state, since the mechanism of vulnerabilities cut across neighbouring states. Ecologists term this phenomenon of interconnectedness nested vulnerability, which Panda explains in the following terms: “(V)ulnerabilities are interdependent through the mechanisms that increase exposure or sensitivity, as well as the processes that affect capacities. Therefore, the vulnerability of people in Bangladesh is not only dependent on the place-specific characteristics of the country from where people are migrating, but also it depends on the factors originating in the Indian region. Changes in the physical factors in India due to climate change may have indirect effects in Bangladesh adding to the current causes of migration.”[39] If this is true of the Ganges, it is equally true of the Nile, which flows through nine different African nations. At the moment, Egypt and Ethiopia have locked horns, with Sudan caught in the middle, over their share of water from this resource, the world’s longest river.

The narratives surrounding the border (or better, the fence, where there is one) tend to follow two different streaks: national and local. The national-level narratives concentrate on issues of national security, counter-insurgency and trade; while the local narratives mostly concern questions of livelihood that the very existence of the border has brought into being, as well as the contingencies of local politics. Duncan McDuie-Ra illustrates the point, citing the case of the India-Bangladesh border in Meghalaya, showing how fencing, integrated border checkpoints and the surveillance of border areas have become the new normal.[40] The India-Bangladesh border must be one of the most lived borders in the world, where fresh negotiations have to be made around it almost every day, since livelihoods crucially depend on its existence. Transgression here is quotidian and the risks vary according to fluctuations in the relationship between the two neighbouring states. Noting that although national history has portrayed the partition as an ‘absolute caesura,’ and more recently as a ‘cultural and personal disaster’ (usually expressed as memoirs); Willem van Schendel argues that in real terms, over these 70 odd years the ties between the ‘borderlanders’ on both sides have never ceased to exist. In his essay, ‘Working through Partition: Making a Living in Bengal Borderlands,’ and subsequently the book Partition as Livelihood, van Schendel narrates how the India-Bangladesh border has opened the path to ‘ways of earning a living’ outside the regular ‘notions of labour as being waged, proletarianized, free, formal-sector, or organized’.[41] Products worth nearly US $2 billion entered Bangladesh as far back as 2004 with the help of informal traders or their agents who physically transport the products across the borders.[42] These items include betel nut, cattle, cement, coal, cotton, firearms, garments, narcotics, jute, people, pharmaceuticals, sugar, timber and wildlife.[43] The smugglers and the border police – Border Security Force of India and Border Guard Bangladesh – play a cat and mouse game that even involves occasional shootouts, although much of this trade happens with the cooperation or at least complicity of the security forces on both sides. Skirmishes between the two forces are also not unknown. To cite a recent example, in October of 2019, India lodged an FIR against a BSF jawan’s killing.[44] India Today, the well-circulated English newsweekly, reports of the regular existence of prostitution corridors on the India-Bangladesh-Nepal border for the trafficking of poor Bangladeshi or Nepalese young women (quite often minors too) to brothels in Kolkata or other cities in India. The traffickers usually hold fake Indian voter cards or other identity proofs. At times, they even purchase small pieces of land on the Indian side of the border where the women are ‘harboured’ for a night before being sold to the brothels.[45]

Meanwhile, the two neighbouring countries – India and Bangladesh – continue to intervene (and in the process, mangle) the lives of the peripheral population. The 4000 km long border with Bangladesh through West Bengal and Assam and the other parts of the North East have made traditional neighbours into citizens of separate states, while work relations remain. What has been separated in maps and official documents is sutured by the daily practice of the local residents. People crisscross the border for daily shopping, hold land on the other side of the border, trade in a large variety of goods (including humans), cattle strays the line causing great harassment to the owner, human bodies are blasted into parts by landmines laid by security forces. But life continues and monies are transacted and made. The border is the supreme expression of the sovereign power of the nation-state and also its daily disavowal. For India, ‘Bangladeshi migrants’ constitute a necessary oppositional category, needed to establish the rootedness of the nation. In the process, what is obliterated is the arbitrary nature of the border that runs through the middle of dusty village roads, endless pools and interlocking paddy fields. The more porous and abortive the border, the more zealous the attempts to master it, the barbed anxieties of official cartography being what they are. The external border is both a reality and a metaphor; together, they produce in myriad ways internal boundaries that fuel politics. It is next to impossible to sieve out a particular community from the flow of people that cross the border. India’s ruling party knows that very well. But they need this disconnect. Mamata Banerjee, the chief minister of West Bengal, also realizes which way Hindu votes will swing with the enactment of CAA in the next election. Hence, the fury, the Halla bol.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

In a conversation with Gunter Grass, Salman Rushdie remarked that the second part of the 20th century would be remembered for two historic developments: the Bomb and mass migration to the Western countries from the ex-colonies.[46] Rushdie’s migrants includes working class migration alright, but he was mainly focused on migrants like him, that is, educated professionals who migrate on volition looking for better opportunities abroad. But working class migration to the West started much earlier with the coming of the plantation raj. Over time, it has only increased, especially since world war two. The twenty-first century will be the century of forced migrants, both inside the country or across international borders. Since today migration is one of the main concerns of the states and international funding and policy organizations, the questions asked are typically statistical and political questions. In the process, the migrant has lost out to migration. As a result, the reality of the act of migration, the act of moving from one point to another, is seldom told, not at least in social sciences. The state machinery and NGOs collect data on who all left point A and reached B. But movement in the line AB can be infinitely divided, where each point is both a point of arrival and point of departure. Together they make up the texture of ambulatory lives and throws light on the ‘minor history’ of migration, a history that includes revolts and resistance[47], as the one the country witnessed at on 13 April when a large group of stuck migrant workers – without food, without shelter – defied police restrictions outside Bandra West Railway Station in Mumbai in their bid to leave for their native places after Modi extended the COVID-19 lockdown till 3 May 2020.

Still on the point of minor histories of the migrant, of state surveillance, coercion, escapes and revolts, allow me to conclude the paper discussing one of the finest novels ever written on these issues in contemporary times. This is none else than J M Coetzee’s Life and Time of Michael K, a novel about a journey and its spiraling denial in war-torn, apartheid South Africa. An introvert gardener with a disfigurement, a harelip, Michael K decides to cart his ailing mother away from the guns of Cape Town towards a hoped-for anonymous life in the abandoned countryside of Prince Albert. Everywhere he goes, the war follows him. The war, the permit, its ubiquitous denial, the fences, military jeeps, riot troops, arrests, labor camps, escapes, hidings, roadblocks and checkpoints: the novel is really about these, a fiction of fences, a nomadic discourse which retreats and roams in the panoptic vast expanses of the Cape. Coetzee’s rudimentary, ascetic and deliberate prose is like the Cape of hard light – hard light, without shadows, without depth. And in the midst of this unforgiving barren landscape, Coetzee engages in a game of transversals and void, meditating on all the primal biopolitical questions of life and living. If the sovereign expression of fragility is the spectacle of excess, an anti-economy, of repeated violence on the body a la Bataille, for Michael K, his excess is his minimalism. A minimalist existence where a man must be ready to live like a beast since the whole surface of South Africa has been surveyed and mapped and marked as zones of exception. K is tried to be contained within bits of barbed wire, with guards on duty. Some try to contain him with euphemism, renaming the sites: ‘This isn’t a prison … Didn’t you hear the policeman telling you it isn’t? This is Jakkalsdrif. This is a camp.’ As one of the supervisors says about K, patronizingly, he has ‘a feel for wire,’ he said. ‘You should go into fencing. There will always be a need for good fencers in this country, no matter what’[48].

[This paper forms a section of a larger paper, “Border Thoughts: Citizenship, Climate Change and Migration in Postcolonial Neoliberal India”, forthcoming in a two-volume collection, State of Democracy in India: Essays on Life and Politics in Contemporary Times, edited by the author (Primus Books, India, 2020)].Notes and References

- Chotu is the common address for a street urchin, usually a child labourer. Desh stands for homeland which could mean nation/country, place one belongs to within a country (district, province) or past land in the sense, the place one is originally from. Perhaps the German word, Heimat comes closer to what desh means than any English equivalent. ↑

- Saskia Sassen, Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014. ↑

- A Wikipedia entry titled, “2013 Bangladesh anti-Hindu violence”, lists thirty four Hindu temples that were attacked between 28 February and 22 March 2013 during an episode of communal violence. The violence apparently was in response to the International Crimes Tribunal sentencing Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, the vice-president of the Jamaat-e-Islami, to death on 28 February, 2013 for war crimes committed during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. The report cites numerous press reports, including BBC News (London) and The Daily Star (Dhaka), in support of its claim. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2013_Bangladesh_anti-Hindu_violence; downloaded 25 February 2020). Another Wikipedia entry, “1989 Bangladesh Pogroms”, claims that during October-November 1989, thousands of Hindu homes and businesses were destroyed as were 400 Hindu temples. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1989_Bangladesh_pogroms; downloaded 25 February 2020) ↑

- “Hindus made up 1.85% of Pakistan’s population according to the 1998 census – although the Pakistan Hindu Council claims there are around 8 million Hindus living in Pakistan, comprising 4% of the Pakistani population. As of 2010, Pakistan has the fifth-largest Hindu population in the world and by 2050 may rise to the fourth-largest Hindu population in the world.” Hinduism in Pakistan, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hinduism_in_Pakistan, downloaded: 22 January 2020.Interestingly, Gulf News reports, Hindus in Pakistan rejected the CAA. See, ‘Hindus of Pakistan reject CAA, do not want Indian Prime Minister Modi’s offer of citizenship’, Golf News, 18 December 2019 (https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/pakistan/hindus-of-pakistan-reject-caa-do-not-want-indian-prime-minister-modis-offer-of-citizenship-1.68552370; downloaded 22 January, 2020) ↑

- Third Definite Article for Perpetual Peace: Cosmopolitan right shall be limited to conditions of universal hospitality.“Here, as in the preceding articles, it is not a question of philanthropy but of right, so that hospitality (hospitableness) means the right of a foreigner not to be treated with hostility because he has arrived on the land of another. The other can turn him away, if this can be done without destroying him, but as long as he behaves peaceably where he is,’ he cannot be treated with hostility. What he can claim is not the right to he a guest (for this a special beneficent pact would be required, making him a member of the household for a certain time), but the right to visit; this right, to present oneself for society, belongs to all human beings by virtue of the right of possession in common of the earth’s surface on which, as a sphere, they cannot disperse infinitely but must finally put up with being near one another; but originally no one had more right than another to be on a place on the earth.” Immanuel Kant, Practical Philosophy, Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. (pp. 328-9).Here is how Kant stipulates import tax: “Certain restrictions on imports are included among these laws, so that the means of acquiring livelihood will promote the subjects’ interests and not the advantage of foreigners or encouragement of others’ industry, since a state, without the prosperity of the people, would not possess enough strength to resist foreign enemies or to maintain itself as a commonwealth.” Kant, “On the common saying: That may be correct in theory, but it is of no use in practice”, ibid, page 298. ↑

- Peter Fitzpatrick, “‘The Desperate Vacuum’: Imperialism and Law in the Experience of Enlightenment”, in Peter Fitzpatrick, Law as Resistance: Modernism, Imperialism, Legalism, London: Ashgate, 2008. ↑

- Stephen Legg and Alexander Vasudevan, “Introduction: Geographies of Nomos” in Stephen Legg edited, Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, London and New York: Routledge, 2011, page 2 ↑

- Antje Ellermann, ‘Discrimination in migration and citizenship’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (Special Issue: Discrimination in Migration and Citizenship), February 2020 (online), page 4 ↑

- Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, Border as Method or the Multiplication of Labour, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2013, page 35 (“In all these gestures of spatial appropriation, tracing boundary lines played a crucial role on private property without enclosure, once could say with Marx or for that matter with Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “the first man, who having enclosed a piece of ground, to whom it occurred to say this is mine, was the true founder of civil society.”) ↑

- Ibid, page 19 ↑

- Etienne Balibar, Politics and the Other Scene (“What is a Border?”), London:Verso, 2002, pp. 75-86 ↑

- Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, ibid, p. 35. ↑

- See Etienne Balibar, ibid, especially page 82 ↑

- Hridayesh Joshi, ‘Climate change now displaces more people than war, and India should be worried’, Quartz India, February 21, 2020 (https://qz.com/india/1806064/india-vulnerable-as-climate-refugees-surge-amid-floods-droughts/; downloaded: 25 March 2020) ↑

- Saskia Sassen, cited above (see ‘The Savage Sorting’, especially pages. 9 – 11) ↑

- Üyesi Burak Gürel, “Dispossession and development in the neoliberal era”, Ankara University SBF Journal, 24 May 2019 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333355601_Dispossession_and_Development_in_the_Neoliberal_Era; downloaded 4 January 2020) ↑

- Mike Davis, Planet of Slums, London: Verso, 2006, page 158. ↑

- Saskia Sassen, cited above, page 12—13 ↑

- Geoff Bailey, ‘Accumulation by dispossession: A critical assessment’, International Socialist Review, Issue #95, https://isreview.org/issue/95/accumulation-dispossession ↑

- Mike Davis, cited above, page 179 ↑

- Mike Davis, page 178 ↑

- Mike Davis, page 151 ↑

- Kalyan Sanyal and Partha Chatterjee, “Rethinking Postcolonial Capitalist Development: A Conversation between Kalyan Sanyal and Partha Chatterjee”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 36, Number 1, May 2016, page 107. ↑

- Mike Davis, ibid, pp 179-180. ↑

- Partha Chatterjee, I am the People: Reflections on Popular Sovereignty Today, New York: Columbia University Press, 2020. ↑

- Himani Chanda, ‘At 1.28% of GDP, India’s expenditure on health is still low although higher than before’, The Print, (https://theprint.in/health/at-1-28-gdp-india-expenditure-on-health-still-low-although-higher-than-before/313702/) (downloaded: 31 March 2020) ↑

- Prachi Gupta, “How much India spends on education: Hint, it’s less than rich countries average”, Financial Express (https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/how-much-india-spends-on-education-hint-its-less-than-rich-countries-average/1772269/) (downloaded: 31 March 2020) ↑

- Sneha Alexander and Vishnu Padmanabhan, “How much does the Indian government spend on women’”, livemint, 8 March 2020. The report continues: “The government estimates these figures by adding all the spending on women-related schemes. This comprises spending on schemes that only target women (Part A), such as Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao, and Part B schemes, which partially target women (where at least 30% of the scheme’s benefits go to women). Between the two, Part B schemes, such as the Mid-Day Meal programme, dominates (around 80% of the gender budget in FY20).” (https://www.livemint.com/news/india/how-much-does-the-indian-government-spend-on-women-11583662675936.html) ↑

- Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘Breaking the Wall of Two Cultures’, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h1DuAvEpMVI ↑

- DTE Staff, ‘Climate change displaced 2.7 million Indians in 2019: Disasters now displace more people than conflicts’, 05 December 2019 (https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/climate-change/climate-change-displaced-2-7-million-indians-in-2019-68291) ↑

- Norman Myers, ‘Environmental Refugees’, Population and Environment, 19(2), 1997 pp. 167-82 in Architesh Panda, ‘Climate Induced Migration from Bangladesh to India: Issues and Challenges’ Conference Paper, UNU summer Academy on social vulnerability 2010 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233751615_Climate_Induced_Migration_from_Bangladesh_to_India_Issues_and_Challenges) ↑

- Elizabeth Ferris, ‘Making sense of climate change, natural disasters, and displacement: a work in progress’, Calcutta Research Group Winter Course, 14 December 2007, page 2 (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1214_climate_change.pdf; downloaded 2 February 2020) ↑

- ibid, pages 4 & 9. ↑

- With kind permission from Elizabeth Ferris. Page 7 ↑

- See, Panda, op cit. ↑

- Jane McAdam, Climate Change, Forced Migration and International Law, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012 (“A country’s level of development is central to its adaptive capacity, since resources and technology increase capacity, while poverty limits it. Thus, although the effects of climate change are indiscriminate, they will be felt more acutely in some parts of the world than in others.”, page 4) ↑

- Norman Myers, ‘Environmental Refugees: A Growing Phenomenon of the 21st Century’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 357(1420): 609-13 in Panda, op. cit. ↑

- Panda, op cit. ↑

- Panda, page 13. ↑

- Duncan McDuie-Ra, “The India–Bangladesh Border Fence: Narratives and Political Possibilities”, Journal of Borderlands Studies, 29.1 – 2014. ↑

- Willem van Schendel, ‘Working Through Partition: Making a Living in the Bengal Borderlands’, IRSH (Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis), 2001, page 397. ↑

- Sujata Ramachandran, ‘Indifference, impotence, and intolerance: transnational Bangladeshis in India’, Global Migration Perspectives, No. 42, Geneva, 2005 in Panda, pages 14-15. ↑

- Duncan McDuie-Ra, page 84. Also see, Anand Kumar, Illegal Bangladeshi Migration to India: Impact on Internal Security, Strategic Analysis, Vol. 35, No. 1, January 2011, 106–119. ↑

- India Today Desk, ‘FIR against Border Guard Bangladesh over BSF jawan’s killing’, India Today, October 19, 2019. https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/fir-against-border-guard-bangladesh-over-bsf-jawan-s-killing-1611017-2019-10-19. ↑

- India Today Desk, ‘Prostitution corridor on Bangladesh border’, India Today, June 23, 2017 (https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/human-traffickers-fake-documents-india-bangladesh-border-984411-2017-06-23; downloaded: 21 March 2020). ↑

- Salman Rushdie, and Gunter Grass, ‘In Conversation: Fictions are Lies that Tell the Truth, The Listener, 27 June 1985, pp. 14-15. ↑

- See, Thomas Nail, The Migrant Figure, Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 2015, pages 14 & 4. ↑

- J M Coetzee, Life and Times of Michael K, London: Vintage Books, 2004, page 95 ↑

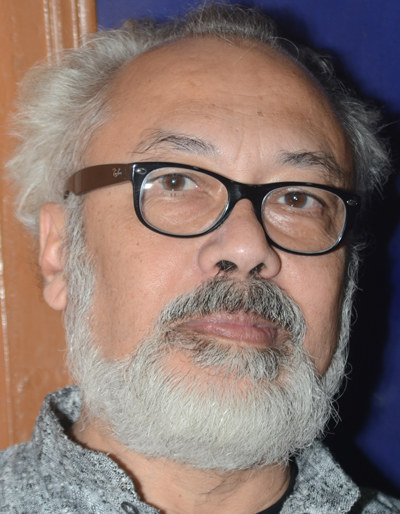

Manas Ray retired as a Professor of Cultural Studies at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC) in March 2018. He works at the interface of political theory and cultural studies and has published on a wide spectrum of areas including Marxism, ethics, governmentality, postmodernism, film theory, New German Cinema, Bollywood, biopolitics, continental political philosophy, critical legal theory, cultural lives of Indian diasporas, and memory and locality of post-partition Calcutta. He has held visiting positions in Berlin, Paris, Edinburgh, Amsterdam and Cape Town. Primus Books is bringing out a two-volume collection edited by Professor Ray entitled, State of Democracy in India: Essays on Life and Politics in Contemporary Times this year.