Perspectives on the Partition in East India after Seventy Years

This essay is an attempt to address the conditions and tendencies in visual arts resulting from the aftermath of the Partition in Bengal through the practices of three artists whose concerns and approaches, driven by a spirit of activism, mark a visible turn in the contemporary art practices in the region. In addition, the essay also tries to shed light on the deeper associations of the artists with the spaces they inhabit and their modes of addressing social discrepancies, class struggles, and citizenship by way of treating art as ‘a matter or truth’ over art as ‘a matter of taste’.

Vinayak Bhattacharya, Inspired from Bhandi, The Border from North 24 Parganas, Grass board relief print, 2015. Photo Credit: The artist.

If Partition is a division that segregates a given piece of land then it is as much a matter of geography, of space and spatiality as it is of history, time and temporality. Rehabilitation of migrants and their conditions of living are still questionable when it comes to their experience of existence. Socio-spatial dialectics have, therefore, become an urgent concern of several artists whose experiences of the Partition over seven decades have become a crucial tool for reclaiming their rights to the city – rights for equality, rights for dignity, rights to a world without discrimination. In this context, the practices of three artists from West Bengal – Vinayak Bhattacharya, Dhrupadi Ghosh, and Anupam Roy, for nearly a decade now, point toward a new approach to the production of art. Not only do they share a rhetorical voice (as opposed to producing purely retinal experiences, or following the traditional mechanisms) but also choose as their subject matter the average, ordinary and the profane, where eternal value, aesthetics, the genius of the artist, mystery and creativity are neutralized in the face of rhetoric and poetics (which are also the quintessential traits of conceptualism).Their modes of working include drawings, prints, sketches, (and seldom paintings) but often include posters and graffiti in order to realize their creative expressions. By relentlessly and critically questioning their predicaments through their practices and by politicizing their works, the artists also disengage from the traditional framework of art production. Also, though they are not activists per se, the work of the three artists is driven by a spirit of activism in the very way in which they engage with their communities and generate a sense of belonging to a space.

The Partition of India along its North-Western and Eastern frontiers is a major concern of artists even to this day. The political chaos and violence following the independence of India was unarguably the catalyst that led to the modern aesthetic and the formation of the Progressive Artists Group in Bombay in December 1947, and the Delhi Shilpi Chakra in 1949. Though formed in 1943, the Calcutta Group of Painters, especially in its later years, had begun to focus more on the social and political realities of the state and nation of the time, rather than following the canonical route to aesthetics. Many of the group’s members expressed growing sympathy towards the Communist Party that was shaping its way through India and some even joined militant activism themselves. As the group’s ideology stemmed from the tragedies including wars, famines, massacres, the Tebhaga Movement of 1946-’47, and the Partition of the country, its manifesto became a synthesis of these experiences that aimed at eschewing religion in art and creating a niche for Indian art to modernize. M. F. Hussain claimed the Partition as the turning point of the country and the emergence of a “new” India. (J. Srivastava, The Paintings by M.F. Husain, 2017) The works of many artists, who bore witness to the Partition – Pran Nath Mago, Satish Gujral, Krishen Khanna, Jimmy Engineer, S. L. Parashar, Anjolie Ela Menon, Jogen Chowdhury, Paritosh Sen – have made long-lasting impressions in the country’s cultural memory on either side of the frontiers. However, the inexplicable mayhem was so overwhelming that it was nearly impossible for the artists to summarize the situation with subtlety.[1]

Subsequently, the subjects addressed by these artists were predominantly documentary – delineations of the exodus, hordes of people, disorder and chaos during the Partition – often literal, realistic portrayals of the situation, and rendered with immediacy. This immediacy, for instance, noted in the works of Pran Nath Mago (Mourners, 1947), and Krishen Khanna (Exodus, 2007), and the Pakistani artist Jimmy Engineer (The Last Burning Train of 1947), and deep scars continue to dominate the works of many artists long after the occurrence of the event (for instance, in the works of Tyeb Mehta).

However, relatively more abstract and subtle expressions on the subject of Partition did not appear until late, often with the second generation of artists, over time and with more vicarious experiences with knowledge gathered from family lores, literature, theatre and cinema. Such poetic expressions can be found in the works of Zarina Hashmi, Nalini Malani, and Shilpa Gupta, among others. Nalini Malani’s installation, for instance, The Tables Have Turned (2008) consisting of thirty-two reverse painted metal turntables cast shadows of a haunting past. Malini’s works have often been informed by the narrations of her grandparents who were forced to uproot themselves during the Partition. She uses trauma as a moment in the history of the nation. (Iyengar 2018) Seventy years later the Partition of India from its neighbouring countries Pakistan and Bangladesh (earlier East-Pakistan) offer deeper perspectives on the echoes of the incident.

II

Partition: A Troubled History of East India and its Impact on Contemporary Artists in Bengal

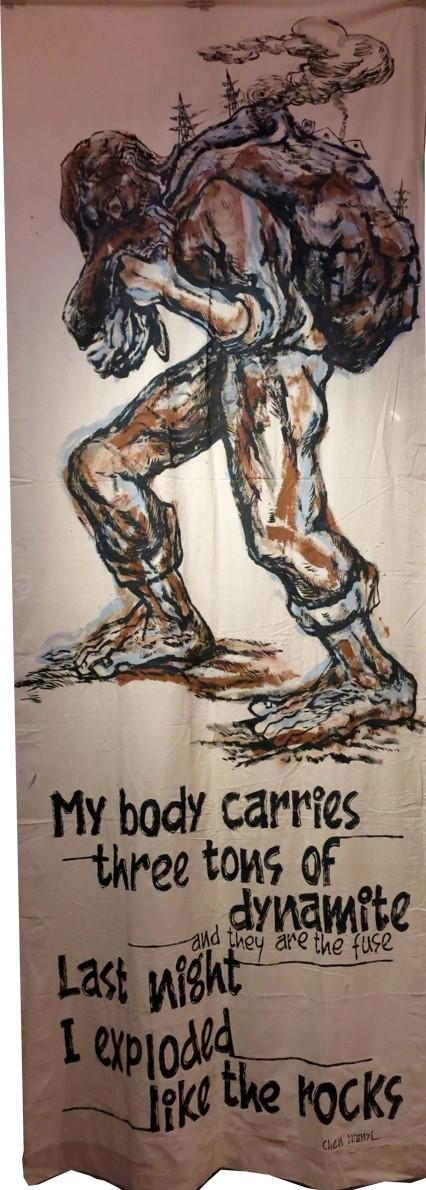

Anupam Roy, Wait,Black pigment and distemper on cloth, 2018. Photo Credit: Project 88, Mumbai

In East India, the history of the Partition takes a different course as it witnesses the influx of refugees in three major successive waves in the 1950s, ’60 and ’70s, following the independence of India in 1947. Infallibly these people were victims of or witnesses to arson, looting, pogroms and rape. The continual influxes along the eastern borders make an even more troubled history attributed to East India when problems pertaining to rehabilitation pave the way for politics of spaces, class struggle, and discrimination that continue to exert an influence on successive generations after nearly a century has passed.[2]

Though the rehabilitated families of East Bengali refugees were able to find themselves a means of survival, a sense of ‘unbelonging’ never left them. Discrimination on the grounds of language, food, and culture seemed to haunt them perpetually. The ‘war’ between ghoti (West Bengalis) and bangal (Bengalis arriving from East Pakistan or Bangladesh) made its way through literature, films, and casual conversations among people and even sport (especially soccer). What made up largely for this void of immigrant East Bengalis is the print culture and their voracious appetite for reading. Subsequently, universities, academics and literature among other cultural activities became their world, where they found their existence meaningful – becoming both consumers and producers of these worlds.[3] From such an irreconcilable beginning, communism became the ultimate ray of hope for hundreds of East Bengali families as the experience of Partition had turned many against the Congress. Debranjan Ghosh, a witness whose life started from one of the refugee colonies recounts:

“…No event occurred where millions of people, for religious reasons had to lose their homeland, had to leave the hearth of their seven ancestors.”

“Congress blamed Partition on the Muslim League (the political party that called for a separate Muslim nation-state to be created at the time of Partition). But the people who worked for Congress in East Bengal, the people who were educated, the people who knew what really happened knew that the Muslim League was not the only party to blame. Congress had a very big role,” he said. “That’s how they became anti-Congress.” (Choudhury c. 2017)

However, recounting of experiences of racial discrimination continue to resonate through successive generations of the immigrants, compelling the latter to relook critically and often with reprobation into their identities and ideologies. They grow increasingly aware of the politics of spaces and the relationship between the people on either side of the borders. Their fractured worlds seem to be an unassailable truth, shaped by the lasting legacy of the Partition.

Artists Vinayak Bhattacharya, Dhrupadi Ghosh and Anupam Roy grew up in families where the experiences of landlessness, nostalgia and disillusionment were part of almost every conversation. Needless to say, the families of the three artists had migrated to India following the Partition of 1947 and its aftermath.

Both Vinayak and Anupam hail from Asoknagar, a small town in the North 24 Parganas in West Bengal, where a major section of East Bengali refugees was rehabilitated.[4] In fact, most places where the immigrants later got themselves settled (called ‘squatter colonies’) – were often non-existent on the official map of the country. Kushanava Choudhury’s account illustrates the architecture of such an unrecognized refugee colony:

“The refugees settled on about 50 acres of land. When the first colony committee allotted plots, they also planned for schools, playing fields, a colony bazaar and neighbourhood clubs. More schools came up, each with its own school committee, all under the umbrella of the colony committee. Just as the state government was building planned townships like Salt Lake with their futuristic nomenclatures, identical water tanks and traffic circles, a different kind of planned community was being developed by the squatters in the colony, with its own organisation, its own order, its own logic. Except [for] none of its initiatives were recognized by the state. On the maps of the government, the colony didn’t exist, its schools didn’t exist, nor its houses.” (Choudhury c. 2017)

Thus, this queer map on which Asoknagar is located draws a clear line between the power structures, arguably stating why the border has to be at the margin.

Dhrupadi Ghosh’s parents, on the other hand, have never felt at home in the city of Kolkata where they had settled down arriving from Barisal and Faridpur. Though they ever since have run a book store where books from Russia and China – echoing our political ties with those countries are still available, a longing for East Bengal continues to linger.

III

Marking the Fissures: Partition, Social Discrepancy, and the Artists in their Formative Years

Vinayak Bhattacharya

Vinayak Bhattacharya, Bangladeshi farmers cross over at the border to their fields in India for farming daily, Photograph, 2014. Photo Credit: The artist

As the un-industrialized Kolkata in the 1990s was a hub of workers unions under the Left Front, impoverished and lacking the promise of development, Delhi was the obvious destiny for aspiring artists such as Vinayak Bhattcharya, for the realization of their dreams. Vinayak set out for Delhi, right after the open-door policies were announced in the country in the year of 1992.

After thirteen years of experiencing the metropolis and going through several personal setbacks, Vinayak could hardly reconcile to the effects of global capitalism that is at once homogenizing, overarching and universalizing. New Delhi – the transforming capital city – was not the place he would feel at home. These lived experiences compelled him to return to Asoknagar and relook at the township of rehabilitated East Bengalis, close to the border between India and Bangladesh and on the fringes of Kolkata.

The artist begins to explore the neighboring areas extensively, especially the borderland between India and Bangladesh, quickly capturing moments of the geography and its inhabitants using his digital camera – he is a trespasser here, and there is dearth of time. The army check-posts; the barbed wires; the desolate landscape; the farmers who cross the borders every day for tilting their shared lands and return to the neighbouring country on their bullock-carts; dead bodies of children and youths temporarily kept inside bamboo-shaft tents – allegedly exterminated by the Border Security Forces for trespassing and hushed up as death by snake-bites: all point toward a porous and yet uncharted world. Bhattacharya here discovers a porous space and demography that compels him to rethink the definition of ‘no man’s land’. He spots children playing on the fields along the barbed-fences; women and children smuggling Phensedyl; he watches flesh-trade and human trafficking in broad daylight. The artist discovers the dynamic ways in which the human body adapts to a given geography, contributing to a thriving economy shaped by the land’s history. He also discovers a novel lingua franca: Urdu written using Bangla fonts and read in the normative reverse order; he finds it on the billboards, in the naïve advertisements for balms and elixirs and handbills. It is a different cosmology altogether – a space of intense cultural osmosis. And for it to take shape, it took a Partition.

As time is a major constraint in these expeditions, the artist, subjected to constant surveillance and suspicion resorted to quicker mediums – brush and ink drawings on postcard sized handmade paper. Between the years 2009-19, a decade-long engagement with the borderland paved the way for an incredibly vast collection of artist’s books, notes, drawings, sketches, and grass-board prints (procured from local hardware) and produced by the artist. The extensive landscape seen through the barbed fences; the vertical and impassive check-posts with their dark silhouettes declaring their stolid presence; a flying bat that covers the background and obstructs visibility – all herald an ominous presence of an Orwellian dystopia, where everything seems to go on spontaneously with equal ambiguity.

Vinayak’s expeditions into this forbidden zone are strategically made possible by his ability to set up elaborate and casual conversations with the locals and the border guards – a process that helped build trust. By taking a deep interest into the lives of others, the artist’s unobtrusive entry into the neighbourhood becomes a catalyst for the communities on both sides of the border to rethink their history with growing awareness about the nuances of their lives.

Dhrupadi Ghosh, Pardon Silence, Performance Still, 2011. Photo Credit: The artist.

Dhrupadi Ghosh

Dhrupadi’s parents were associated with the Naxalite movement during the 1980s and ’90s and would often participate in protests upholding the rights of the landless and the underprivileged, such as during Operation Sunshine[5], in Kolkata. These engagements were the impetus for a young Dhrupadi during her university years at Kalabhavana, Santiniketan to be a part of several local protest movements by farmers against corporate land sharks – the Jomi Andolan and Lal Bandh Andolan and would even bring relief to the victims. In addition, she came into contact with an ambience where the influences of theatre director Badal Sarkar and his anti-establishment plays during the Naxalite movement continued to resonate among the later generations. These experiences were instrumental for Dhrupadi in organizing and mobilizing the masses. Also, during the 2010s, her concerns for the Kashmiris came to be realized through the posters that she made (which were even displayed in at least one commercial exhibition in Kolkata).[6]

Dhrupadi decides to leave Kolkata for New Delhi (c. 2010) after attending an artists’ residency at Sarai-CSDS[7]. During her stay at Sarai she came in touch with the lower rung of society in New Delhi: tailors, bakers, tea-vendors, grocers. The period was ripe for her joining the Jamia Millia Islamia, first as a Guest Faculty in the Fine Arts Department and later as a Research Fellow in the Department of Sociology, after she felt that it is people who matter the most. The ‘Jamia period’ is crucial for her witnessing the rise of the Communist left-wing Muslim students, many of who had come from Kashmir and with whom she became actively involved, resulting shortly in her removal from the institution.

Dhrupadi went underground for nearly a year as a consequence. Each of her nights was spent at a different friend’s place, being constantly hounded by the police. She becomes a victim of psychotic symptoms, a consequence of deep anxiety and trauma. She resorts to frenzied sketches and pen and ink drawings, filling up the pages of her diaries with images of policemen; burqa clad women; struggling men and women; children and people huddled in corners or people without a sense of purpose. She gets in touch with workers, people of the minority communities where she goes to quickly eat her meals. She meets them on her way to another friend’s place. She withholds contact with her parents for an unknown time.

A sense of relief seemed impossible till Dhrupadi managed to reach Kolkata before the Covid-19 crisis and reunited with her family. The plight of the migrant workers, a close watch on an ailing mother, a close-circuit camera, a pork chop that she had cooked for lunch become her subject-matter now, indicating an inward turn. However, back home, she resorts to social media for fiercely fighting for the rights of the migrant labourers, the powerless and the disposed; and organizes regular conversation with her comrades over webinars. She even begins to promote clothes via social media, sold by Kashmiri Muslim clothes vendors in Delhi as a take against corporate capitalism. In addition, she organizes a temporary canteen with her neighbours for supplying food to the affected workers during the lockdown. A strong sense of community is created by her organizational interests.

Anupam Roy

Anupam Roy, Resistance Land, Ink on paper pasted on cotton cloth, 2018. Photo Credit: Project 88, Mumbai

Anupam Roy, who had spent most of his childhood witnessing his East Bengali mother suffer endless humiliation at her in-laws’ on grounds of caste, class, and culture differences and especially for her dialect – Bangal, finally moved to stay with his maternal grandparents in the township of Asoknagar, for escaping discrimination. The experience had a long-lasting effect on Anupam, who developed a deep sense of insecurity almost inherently, that continued to reflect on his canvases during his college years. In fact, zoomorphic animals devouring an innocent man became a recurrent subject of his paintings during the formative years.

For Anupam, drawing wall graffiti began at a very young age as an amateur artist assisting his art teacher. He grew up marking the discrepancies of growth between the suburbs of Asoknagar and the city of Kolkata, under the Left Front. Underdevelopment, lack of opportunity for jobs and an age-old education system classified the margins of the city, while the urban academia was ruled by staunch CPI (M) supporters. Such an abhorrence for the ruling Left Front motivated him to draw posters in support of the victimized farmers of Singur and Nandigram, who had fallen prey to the governmental policy of implementing SEZ laws, coercing them to give up their lands for the sake of corporate capitalism, in the Hooghly and East Midnapore districts of West Bengal. The artist soon began to enjoy the power and process of poster making – images drawn using zinc and charcoal and sticking these up on the walls of shops around the local market.

The sheer appeal of holding public attention and the robustness of the process was hard to get over. Driven by this impetus, Anupam decided to work in advertisement agencies and moved to New Delhi in 2008, where he soon got involved with the CPI(ML) Liberation and the left-wing students’ body AISA,[8] and other land related movements. The following years saw him taking part in countless workers and trade union protest rallies, marches, and rigorously producing large-scale posters and wall graffiti for AISA – an engagement that is collective in spirit. His anxieties about isolation, rootlessness and an urgency of belonging was now realized through his association to a political party which brought a deeper sense of community. He also travelled extensively to Allahabad, Lucknow, and Patna, among other Indian cities, for the party’s political propaganda for which he drew large scale posters, and became increasingly aware of how the role of an artist transforms into that of a protester: one who make posters, becomes part of a rally, and is beaten up by authorities. Posters, therefore, do not belong to their makers alone but become collective forms of communication. The years between 2008-14 were instrumental in Anupam engaging with literature, culture, world cinema and politics – which assisted him to understand the fissures and complexities of class struggle in society. He also took a keen interest in the politics of representation and the equations between land, eviction, privatization and ownership, among other things. These culminated into a series of exhibitions based on the themes of displacement and migration at the Halisahar Sanskriti Sanstha, in North 24 Parganas of West Bengal for the next couple of years. During the same period, he filled up the village of Charmahatpur near Dhubulia in Nadia district almost in its entirety with posters and graffiti following the farmers’ protest movement.

These experiences on the part of the artists are instrumental for questioning their positionalities within a society where each of the artists is still ‘an outsider’ and struggles to reclaim a space. The history of Partition becomes the rhetoric for questioning class-struggle, fixed notions of ‘land’, re-looking into histories of the subaltern, and the politics of representation. The artists re-negotiate with their spaces of habitation through this rhetoric.

IV

Justifying Existence: Asserting One’s Rights to Spaces of Habitation through Creative and Collective Engagements

Anupam Roy, Those Who Do Not Give Up, Black pigment and distemper on paper, 2018. Photo Credit: Srijan Biswas

Rights to one’s city is more than just the rights to access the city’s resources or improving one’s housing or surroundings. David Harvey argues that “one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights – the rights to the city is also about the freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves.” (Harvey n.d.) It is interesting to note that though the three artists have rarely crossed paths, they are similar in their approaches when it comes to reclaiming their spaces functionally and creatively through collective and collaborative initiatives in their communities. And though the artists visit their homelands only occasionally (except Vinayak who has moved permanently to Asoknagar), each of the three artists found it urgent to start their own spaces engaging more people. Anupam Roy restarts an artists’ residency at Banipur near Asoknagar, a local community based artists’ initiative which supports rigorous research on tracing the histories of the subaltern and addresses contemporary realities. Anupam runs the collective with fellow artists Ashish Dhali, Rocky Majumdar, Subhashis Gayen and Tushar Kanti Saha. Ashis Dhali is also an artist-in-residence, among others, supported by the organization in Banipur, who has been researching on the history of the Matua Mahasangha, a 19th century religious reformation movement of the Namashudra community. The residency also periodically organizes poetry conferences, performances and artists’ workshops.

Dhrupadi Ghosh starts an artists’ collective – New Observationists with Latin Americans artists that aims at a shared network with the Cadáver Exquisito, (Latin for the Exquisite Corpse) all across the world. She also is an illustrator for Critical Edges, an anti-capitalist magazine brought out from Copenhagen by students who thrive on the leftovers of the wealthy: food, clothes and more. The artist also makes good use of social media to voice her concerns out. Vinayak Bhattacharya, on the other hand, embarks on various self-initiated activities that are truly emancipatory in nature and ignore particular identities by way of fraternizing a community’s members. He engages children and adults to paint on the streets every week. He also activates the civic bodies – the local municipality, schools, the library and clubs to support more creative expressions that realize life along the borders and the changing city. Brittangsho is an unrealized organization that Bhattacharya wants to bring up in the future for encouraging critical discussions on the transformation of urban space and contemporary realities.

Marked by the spirit of activism, a collectivized mode of working, voicing for the powerless, a rigorous engagement with their communities, extensive travels, and the artists’ steadfast reliance on academics and socialism, the practices of the three artists clearly indicate a new visible turn. Their roles become even more intriguing in the way in which they become an intermediate mechanism for reclamation (of space) and of reasserting rights. Unlike their predecessors in the field of art, who had attempted to reconcile with their experiences of the Partition through artworks (primarily paintings), the three artists act as agents of critique of their own times: Can the status quo be overthrown? What constitutes the margin? How can the past be repurposed? How to create a more sustainable future? What transforms the spaces around us? The issues which the artists address is often common to the three of them and are urgent.

Dhrupadi Ghosh, Untitled, Ink on paper, 2019. Photo Credit: The artist.

In fact, a certain critical activism in contemporary art had begun to make its presence felt through a return to collective and collaborative production and had already been pointed out by Okwei Enwezor in his essay The Artist as Producer in Times of Crisis (2004). Enwezor had also felt the possibility of such modes of production as an acknowledgment of the repressed memory of a social unconscious in the face of global capitalism.

“… a visible turn that has become increasingly evident in the field of culture at large, that is the extent to which a certain critical activism in contemporary art has become a way to pose the questions raised seventy years ago anew through collective practices….To that end, recent confrontations within the field of contemporary art have precipitated an awareness that there have emerged in increasing numbers, within the last decade, new critical, artistic formations that foreground and privilege the mode of collective and collaborative production. Is this return an acknowledgment of the repressed memory of a social unconscious? Is the collectivization of artistic production not a critique of the poverty of the language of contemporary art in the face of large-scale commodification of culture which have merged the identity of the artist with the corporate logo of global capitalism?” (Enwezor 2004)

By developing an understanding of how social production functions, the three artists assert their rights to the spaces of their habitation, turning these for imaginative uses by the members of their communities and remaking a world that is more humane, accessible and livable. In fact, such initiatives are not too remote from the ideas of Henri Lefebvre’s plan for a more inclusive city. Lefebvre is insistent on designing a city that considers, incorporates and promotes the importance of making space to include the values, diverse practices and the creative potential of everyday life – elements for reimagining and remaking the city. The idea of ‘the right to the city’ is undoubtedly a challenge to the hegemonic orthodoxy of the homogenizing practices: planning, design, commerce, and the overarching concern with risk assessment and avoidance, surveillance, order and security, and the needs of capital to create conditions for maximising profit. Lefebvre seeks a rebalancing of the right to inhabit and make space from these homogenizing practices rather than merely be the subject, and points out that space can be remade through social practice. By providing “opportunities for play, for the festival, for the imaginative use of the public and social spaces of the city to ensure that it becomes a living space rather than a sterile monotony of function over fun, exchange over use value, profit over people.” (Zieleniec 2018)

V

Whose Interest is Represented?

Vinayak Bhattacharya, Boat from Ghojadanga, Ichamati River, Grass board relief print, 2015. Photo Credit: The artist.

The dynamic modes in which the three artists engage with their activities compels one to think who the spectators of these artworks are; whose interest do they represent and is there a new aesthetic on the horizon? Such queries are also obvious as a conspicuous absence of commercial interest is apparent among the three artists[9].

Often the safe niches of the studio are not the site of production of art works for the three artists and are far from being their private and meditative reflections. This is especially true in the case of Anupam and Dhrupadi, who have primarily worked in a propagandist mode, using posters or set upon nocturnal adventures with spray cans for creating graffiti and slogans: the purposes of which are associated with political campaigns for specific groups and are transitory. In general, the artworks have been produced on the go, often on the spot, and in the public domain. Thus, they have been rendered on smaller formats (such as in diaries, postcard sized handmade paper: more akin to a chronicler’s accounts, in the case of Vinayak and Dhrupadi), accompanying a certain frenzied restlessness. The ceaselessly active worlds of the three artists defy the traditional framework of art production. These artworks are, therefore, not ‘objects of contemplation’ and thus, their value is not eternal and certainly do not call for attention to contemplate the artistic genius. Nor are they meant for private ownership as they are far from being merely commercially oriented.

The fast pace at which the artworks are executed, indicate an inevitable immediacy of purpose. The artworks of these artists seem to be standing as testimonies to their rhetoric while they express endless quests about social discrepancies; living conditions of people and vocalizing the needs of the oppressed (often the masses are involved beyond the artworks). In this context, the modes of working of the artists may be associated with that of Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915-1978), whose vast collection of pen and ink post-card sized sketches and drawings of the hardship of the masses, especially during the Bengal Famine of 1943-’44 were produced as a forceful outcry against the tyranny of domination. These drawings and sketches were undoubtedly documentary in nature and an indictment of the times; rendered during the artist’s hectic travel schedules across the country, especially in undivided Bengal.

The three artists’ questioning the socio-spatial dialectics in the perspective of Partition and seeking a way to reconcile with their present predicament are keys to understanding a crucial visual turn in the artistic practices of Bengal. In addition, their modus operandi is not too remote from the solutions offered by Slavoj Žižek in his seminal essay Answers to Today’s Crisis: A Leninist View:

“One should begin by organizing events of fraternization across the imposed divisions, establishing shared organizational networks…This may sound utopian, but it is only such “crazy” acts that can confer on the protests a true emancipatory dimension. Otherwise, we will get just the conflict of nationalist passions manipulated by oligarchs who lurk in the background. Such geopolitical games for the spheres of influence are of no interest whatsoever to the authentic emancipatory politics.” (Žižek 2014)

If the history of the Partition still poses intriguing questions about identities and citizenship after seventy years of its occurrence, then disorientation is not an effect it has been able to obliterate. If a sense of belonging is still not strong enough among the rehabilitated masses, then the artists’ claim to the city through mobilization, shared networks, working as agents of celebration of their communities’ histories are activities too strong to ignore, so much as the vast collections of their artworks. Art, according to Boris Groys, is either a matter of taste or a matter of truth. In case of the former, art prioritizes the spectator over the artist, thereby losing its independence and power. It is treated ‘in terms of the art market’ (Groys 2016). However, art becomes true when it is directed toward creating social consciousness. The works of Vinayak Bhattacharya, Dhrupadi Ghosh and Anupam Roy begin with the rhetoric on power, land, people and their struggles. Their artworks are more about empowering the spectator about his/her own rights and for questioning his/her position in the power struggle – in short, these artworks change the consciousness of the people. To ignore this visible turn of contemporary art practices towards evolving poetic instruments of communication in the context of Bengal, where Modernist art still holds sway, would be a serious mistake.

Notes

- Some of these artists, such as Satish Gujral was born in Jhelum in undivided Punjab under British India and went to the Mayo School of Arts in Lahore to study Applied Arts. Pran Nath Mago was born in Gujarkhan, a small town near Rawalpindi in western Pakistan in 1923. His family had to leave for Amritsar, a safe haven for many, in an army vehicle during the communal frenzy of 1947 (Singh n.d.). Kishen Khanna was born in Lyallpur, a district now called Faislabad in Pakistan. Anjolie Ela Menon’s memories of the violence in the wake of the Partition keep haunting her even to this day. ↑

- During the independence of India, the influx of immigrants who entered India from East Pakistan were majorly Hindu Bengalis, later taking shelter majorly in the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Tripura. The Noakhali and Borisal Riots in the 1950s saw a steady rise of immigrants who crossed into West Bengal. Migration continued till the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 with more unrest during the years 1964 and ’65, following the East Pakistan Riots and the Indo-PakistanWar, respectively. Source: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Bengali_refugees. Accessed on 17 November, 2020. ↑

- Many notable poets and authors such as Jibanananda Das, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Buddhadeb Bose (moved to India in 1931) and Amartya Sen are from Bangladesh, who have made major contributions to the Bengali literary culture and society and are academic giants in their disciplinary fields. ↑

- ‘A district-wise break-up in 1971, shows the main thrust of the refugee influx was in 24Parganas (22.3% of the total refugees), Nadia (20.3%), Bankura (19.1%) and Kolkata (12.9%).’ Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_Bengali_refugees.Accessed on 17 November, 2020. ↑

- Operation Sunshine was an initiative of the Left Front government implemented in 1996 for the eviction of hawkers from the streets of Kolkata who had encroached on them illegally. This was an after effect of the Partition, which led to the escalating of the refugee population by nearly nine times within 1981. ↑

- Existence, an exhibition curated by SaikatSurai, Gandhara Art Gallery, Kolkata, 2010. ↑

- Sarai-CSDS an initiative of the Raqs Media Collective and City as Studio is a platform for research and reflection on the transformation of urban space looking into the relationships between cities, information, society, technology, and culture. ↑

- All India Students’ Association (AISA) is affiliated to the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation and describes itself as “the voice of the radical students’ movement.” ↑

- Vinayak Bhattacharya’s major exhibitions in commercial galleries, since his return to Kolkata, include Invisible Visibilities (OED, Kochi,2008); The Way We Are (Mon Art Galerie, Kolkata, 2010); Black and White, a group exhibition organized by the Print Making department of Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan in November 2013, and his latest group exhibition at the ICCR gallery in Kolkata (2016), were not commercial exhibitions per se.Anupam Roy’s exhibitions in the commercial gallery include Songs for Sabotage (4th New Museum Triennale, NY, 2018) and a solo, De-Notified Land (Project ’88, Mumbai, 2019). His long-term engagement as a graffiti artist for AISA’s political campaigns was his primary concern before these two exhibitions in the commercial space in recent years.Though Dhrupadi Ghosh’s works have been widely displayed in festivals and as part of exchange programmes, workshops, and artists’ residencies namely in India, France and China, The Story of Multiples (Emami Chisel Art, Kolkata, 2010) and Existence (curated by SaikatSurai, Gandhara Art Gallery, Kolkata, 2010) seem to be the only notable exhibitions in the commercial gallery in the current decade. The conspicuous absence of the three artists from the commercial gallery indicate a curious statistic of their associations with the commercial circuit when compared with their enthusiasm for exploring and questioning life; the frequency of their travels and their engagement with community life.↑

References

Choudhury, Kushanava. History Extra. c. 2017. https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/after-Partition-colony-politics-and-the-rise-of-communism-in-bengal/ (Accessed on November 15, 2020).

Enwezor, Okwei. The Artist as Producer in Times of Crisis. 2004.

Groys, Boris. e-flux. March 2016. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/71/60513/the-truth-of-art/ (Accessed on November 24 , 2020).

Harvey, David. “What is the Right to the City?” Right to the City. https://www.waronwant.org/righttothecity/what.html (Accessed on November 25, 2020).

Iyengar, Radhika. The Mint. September 17, 2018. https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/0t2qPHbXK8BLKPsB0GbHZM/Nalini-Malani-A-memoirist-for-the-Subaltern.html (Accessed on November 25, 2020).

Singh, Prem. “In Remembrance: Pran Nath Mago: An Artist of Our Times (1923-2006).” Remembrance. Vols. 14, Issue: 1. Punjab.

Srivastava, Jyoti. 2017:AIC:INDIA MODERN. 2017. http://www.publicartinchicago.com/2017-aic-asian-galleries-india-modern-the-paintings-by-m-f-husain/.

Public Art in Chicago. September 18, 2017. http://www.publicartinchicago.com/2017-aic-asian-galleries-india-modern-the-paintings-by-m-f-husain/ (Accessed on November 10, 2020).

Zieleniec, Andrzej. “Lefebvre’s Politics of Space: Planning the Urban as Oeuvre.” Cogitatio 3, no. 3 (2018): Urban Planning, 5–15.Žižek, Slavoj. Answer to Today’s Crisis: A Leninist View. PDF. 2014.

Oindrilla Maity is an independent curator and research scholar who has recently submitted her PhD thesis at the Department of Culture Studies, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. She has graduated from the Gwangju Biennale International Curatorial Programme (2012). Her essay in Bangla on the 19th century Bengali reformer, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar has been brought out in the academic volume, ‘Janmadwishatabarshe Vidyasagar’ by Ananda Publishers, Kolkata, last September. Her major anthropological curatorial ventures includes “Tracing a Human Trail: Metaphors of the Frontiers” ( Khoj, New Delhi, 2011) among others.