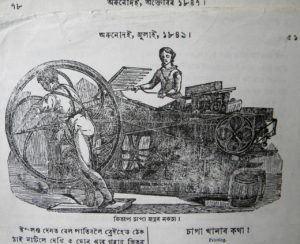

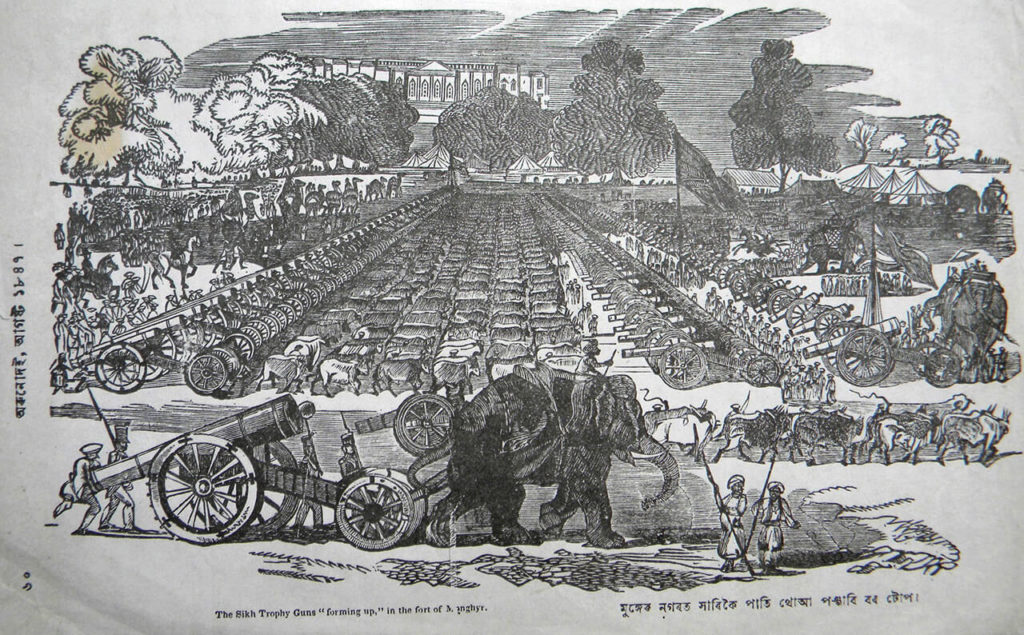

Orunodoi Print, The Sikhs Trophy Gun forming up in the front of Monghyr, (Engraver, Young), Wood Engraving, August, 1847

For British imperial geography, Northeast India was a significant military borderland between the lands of the East India Company and the kingdoms of China and Burma, besides being strategic for the opium and tea trade routes. In 1826, Assam was handed over to the British East India Company with the Treaty of Yandabo, and became part of the Bengal Presidency. The transformations that the British brought to the Northeast as part of its colonial plans of evangelism, trade and capitalism has been manifold, and central to this has been the role of the printing press. With the coming of the American Baptist Missionaries in 1836 in Assam, print media became the catalyst for debate around modernity and public opinion, along with the relationship between authority, nationalism and public discourse. In particular, the first Assamese periodical Orunodoi (Dawn of the Day) published from January 1846 to December 1880, has been instrumental in shaping this modern sensibility. It is also a historical document which can be read in terms of its contribution to the visual culture of colonialism and the beginning of graphic arts in Assam.

Originally, Northeast India was comprised of undivided Assam and the independent princely states of Manipur and Tripura. Being the gateway to the region, Assam has a rich cultural history that can be traced back to the 7th century AD. The earliest literary evidence of the art of Assam is traced to royal gifts presented to Hiuen Tsang and Harshavardhana by Kumar Bhaskaravarman, the king of Kamrupa.[1] The gifts included colored or painted cloth in the pattern of jasmine flowers, and carved boxes for painting and brushes.[2] The Nidhanpur plates (a set of copper plates inscribed in Sanskrit) dates to the same century and offers material from the Kamrupa kingdom along with the written records of Hiuen Tsang. This kingdom had trade relations with the ancient Guptas,[3] and references to wall murals, chitrakars and patuas are found in Assamese literature of the medieval period.[4] Archeological explorations have also revealed rich examples of primitive rock engravings and ancient temple sculptures. In particular, the Ahom Kingdom (1228 – 1826) provided a firm royal patronage of 600 years that shaped its assimilative cultural character and we find architecture, murals, traditional sculptures, manuscript painting, and crafts flourishing in this period.

To trace the trajectories of the role of the printing press and modernity, the years of 1793 and 1813 become significant in this context. William Carey, the founder of the English Baptist Missionary Society (1792) arrived in India in 1793 and was instrumental in spreading Christianity in several provinces in India. Headquartered from 1800 at Serampore (near Calcutta), he established the Baptist Mission Press with William Ward and Joshua Marshman and engaged in translating the Bible to Sanskrit, Bengali and Assamese, among other Indian languages. In 1813, the Charter Act was passed (first formulated in 1793) which offered residence licenses to European missionaries along with the responsibility of ‘social reform, religious education, and moral improvement’ to Indian people,[5] allowing for the growth of evangelism in the following years. Krishna Chandra Pal, the first Bengali Christian, began evangelical work in the Khasi and Jaintia Hills in 1813; however, it was not the British or American Baptists who were the first missionaries in the Northeast – the Portuguese Jesuit Priests arrived in 1627 to set the task for their religious agenda.

In April 1818, the Serampore press published their first monthly journal Digdarshan in Bengali, followed by the weekly newspaper Samachar Darpan in the following month.[6] William Carey and his team were careful to present these publications as secular ones that imparted general knowledge on various subjects, and avoided political discussions. The success of these vernacular publications encouraged the growth of the vernacular press in Calcutta and set the precedent of Christian missionaries supporting such endeavors across colonial centres in India. It was through the activities of Serampore Mission Press that Assam received its Christian incitement through the efforts of British and American Baptist Missionaries, who moved beyond evangelist practices to the realm of education and language. The British Baptists set their mission in Guwahati in 1829 with James Rae establishing an Anglo-Bengali school in 1830, but this mission closed down in 1836 as they could not expand their influence in the socio-cultural sphere because of economic constraints.[7]

As part of colonial administrative policy, the Bengali language was introduced in 1836 as the official language of Assam and became the medium of instruction in courts and schools till 1873. The annexation of Bengali speaking districts of Sylhet, Cachar and Goalpara to Assam in 1874, the reorganization in 1905 to Eastern Bengal and Assam (with more Bengali districts including Jalpaiguri), and the reversal of this Partition in 1911 had a lasting influence on the linguistic antagonism till 1947, and in post-colonial Assam. The role of the American Baptist Missionaries (from the mid-1830s) becomes significant as they rallied for the Assamese language to be used in schools and publications, including Orunodoi, creating public opinion around official recognition and legitimacy, to which the Assamese middle class responded in their literary field and cultural nationalism.

The American Baptists entered Assam with political and commercial intent, apart from evangelist pursuits as they wanted access to the lands of Southeast Asia and China to further the colonial project amongst the Burmese tribes and Chinese populace. The geography of Assam and its multi-lingualism made this pan-Asian project an impossibility,[8] and settling in Sadiya in 1836, the first American Baptist families of Nathan Brown and Oliver Cutter established their mission and brought the first printing press. They also discovered that the languages in Sadiya were different from Burmese, including Assamese which at first had appeared to be a dialect of the Bengali language. They were later joined by other missionary linguists who learnt Assamese among other local tribal languages, and decided to establish mission schools to impart vernacular education to transfer the principles of Christianity and challenge Brahmanical Hindu dominance. The Khamti tribe rebellion in 1839 led to the closure of the Sadiya Mission, after which the Baptists relocated to Sibsagar in 1841 and concentrated on missionary work in the Brahmaputra Valley.[9]

While British policy had initiated the Bengali language to be used in government schools, the schools begun by the American missionaries in the important centres of Gauhati, Sibsagar and Nowgaon imparted Assamese as the tool of instruction. The Sibsagar Mission Press had the facilities to print in Assamese, Bengali and English.[10] Curricular material for the missionary schools were also published in this press, and to elucidate further:

“According to the report of 1851, at the mission press of Sibsagar were printed the New Testament in Assamese, a second and enlarged edition of the Hymn Book in Assamese whose 3000 copies were also been issued, and the Geography of Asia, with maps and illustrations, 1000 copies of which had been published by 1851. Also there were number of books that were published and put on sale at the Sibsagar Mission Press. It was thus generally hoped by the American Baptist missionaries, that the printing press which had proved to be a powerful instrument in other lands, may be fully utilized in the work of enlightenment in Assam as well.”[11]

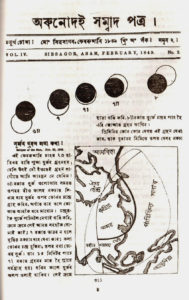

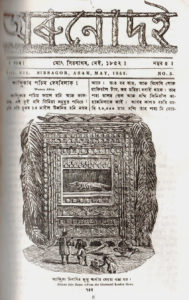

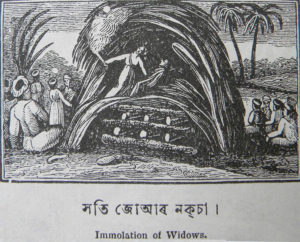

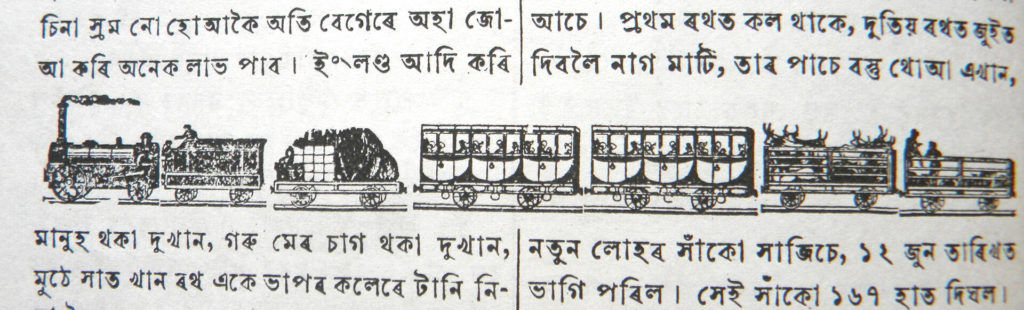

With the British language policy, the Sibsagar Mission Press did not have government support to print vernacular literature till 1874 when it became the Chief Commissioner’s Province and until then, this press was the centre of printing in Assam. It followed the editorial policy of Digdarshan and Samachar Darpan emulating 18th century ideas of European enlightenment, maintaining a high editorial standard throughout the years. It offered new ways of seeing and understanding the world – a modern view of geography with Europe as the centre of progressive thought. In an analysis of the first publication of Orunodoi in 1846 which had twelve issues, Charvak Mukhopadhyay writes of three categories: General Intelligence (32 percent), Religious Intelligence (2.5 percent), Science and Geography; the Solar System; Physics, Chemistry and Technology; Science of Health; and moral fables, narratives of other lands etc. (66 percent with headlines).[12] There were also poems, riddles, embroidery designs, and illustrations with woodcuts copied from the engravings of the Illustrated London News (observed by E.A. Gait in 1897).[13] Orunodoi was subscribed by both Assamese intelligentsia and Europeans, and for the benefit of the latter, the articles and news items had subtitles in English.[14] The Baptist missionaries made every effort to circulate this journal amongst the masses and villages; thus Orunodoi became quintessential of Assamese Renaissance trends.

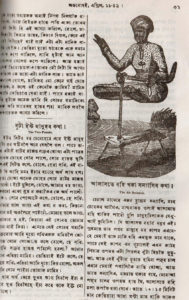

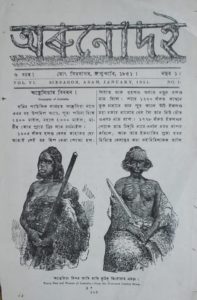

News pertaining to the northeast was of key importance followed by those of the European Empire, the rest of India, Africa and America.[15] The illustrated woodcuts showcased tribal people of distant lands including Australia and this anthropological dimension of Orunodoi led to the construction of identity, “the ‘self’ and the ‘other’, of ‘our own area’ and the ‘other countries’ including the Empire and its ‘other colonies’, apart from bringing basic science and social science to the readers as another important aspect of modernity.”[16] The Desh Bidesh Sanbad in this journal opened the world to the Assamese reader,[17] and the upholding of modern rationalism against superstition, the ill-effects of opium on the populace, the need for social reforms in marriage and position of women, changed minds dramatically.

While all this proved to expand worldviews, the evangelist ideas remained biased towards Christian theology, sexual mores which did not adhere to Hindu and Christian morality were seen as debased, and at the same time the Bengali language transformed to being the language of the colonizers. It was in 1874 that the Assamese language was restored as the medium of instruction in schools, courts and government offices, through political assertions and popular discourse in the public sphere led by the local middle class intelligentsia.

The publication of Assamese manuscripts in Orunodoi was another important endeavor of the American Baptist missionaries, and a large number of Assamese and Sanskrit puthis were collected by the early missionaries in the 1840s-50s in Sibsagar and Nowgaon.[18] In 1915, they were transferred to Gauhati and were worked upon by Dr. S.K. Bhuyan – and many Buranjis like the Purani Asam Buranji, the Dodhai Asam Buranji, Kamrupar Buranji, Lakshmi Singhar Buranji,[19] and the legendary Chutia Rajar Vamsavalli[20] among others, were published in this journal. Orunodoi promoted numismatic study by publishing the fascimiles of quite a large number of coins of Ahom and Koch monarchs and Mughal emperors, found in Assam.[21] The journal also published first ethnological studies in Assamese of the tribes of Assam, along with news of the explorations of commercial resources like tea and coal.[22]

In the realm of visual culture, it was in Orunodoi that the art-illustrations in wood-block relief printing were introduced (for the first time) and reflected all the characteristics of British Academic Realism.[23] Nathan Brown as the first editor of this journal was also a proficient printmaker and some research point to names who carved the wood-blocks for printing as well. There are two kinds of styles that one witnesses in the prints of Orunodoi; firstly, some illustrations copied the style of European journals such as the Illustrated London News, in both subject-matter and craftsmanship of the 19th century printing production process.[24] Secondly, others illustrate the influence of Indian manuscript traditions and also folk painting traditions.[25] This woodblock printing activity could not be sustained locally by the American Baptist missionaries due to funding restrictions, which did not support artistic activity. These unknown wood-engravers who contributed to Orunodoi are now acknowledged to have inspired book-illustrations and printmaking in Assam,[26] in techniques that are European yet interpreting local geography, history and culture.

Notes and References

- Meghali Goswami, Folk and Traditional Art of Assam, Feature, Art & Deal Magazine, February 2013 ↑

- Raj Kumar Mazinder, Voices from the Margin: A Study of Present Scenario of Art Education and Practice in Northeast India, 2018 ↑

- David Ludden, Where is Assam?, Himal South Asian Magazine, November 2005, www.himalmag.com ↑

- Goswami, op.cit., Art & Deal Magazine, February 2013 ↑

- Nathan Brown (Ed.), Maheswar Neog (Re.Ed.), Orunodoi 1846-1854: A Monthly Paper devoted to Religion, Science and General Intelligence, Publication Board Assam, 2008. ↑

- Tilottoma Misra, Social Criticism in Nineteenth Century Assamese Writing: The Orunodoi, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. XX, No.37, September 14, 1985. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Anupama Ghosh, Evangelism in Assam: Schools and Print Culture (1830s-1890s), Indian History Congress, Vol. 75, 2014. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Charvak Mukhopadhyay, Print Media Comes to North East India, Global Media Journal, Vol. 6, No 1&2, University of Calcutta, 2015. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Anupama Ghosh, Evangelism in Assam: Schools and Print Culture (1830s-1890s), Indian History Congress, Vol. 75, 2014. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Nathan Brown (Ed.), Maheswar Neog (Re.Ed.), Orunodoi 1846-1854: A Monthly Paper devoted to Religion, Science and General Intelligence, Publication Board Assam, 2008. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Raj Kumar Mazinder, The Orunodoi and Nineteenth-Century Wood-block Prints from Assam – A Brief Overview, Nezine, 2015 ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

Amrita Gupta is Co-founder and Executive Editor at Partition Studies Quarterly. An art historian and writer, she is involved in art education, archiving and cultural management. With roots in Shillong and a research interest in the visual culture of northeast India, she has documented its art history with a focus on Assam. Her art writings have been published in edited books, journals and websites. She is program director at Mohile Parikh Center, Mumbai, with curatorial interests in socially engaged art and creative placemaking.