Despite the passage of more than seven decades since the partition of India, its history is still to be settled. While the preponderance in partition scholarship favours Punjab and Bengal, Northeast India with its varied experiences of prolonged partitions has not become part of mainstream Indian partition discourse as it should be. Claiming that Northeast India, especially south Assam was as much part of the processes and politics of the partition of India, this essay seeks to engage with the role and contribution of the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind and its leader, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani, a Sufi from Deoband related to the Chisti- Sabiri order.

CitationThe idea of history has primarily been made to appear linear and homogeneous locating itself on binaries and stereotypes which are more of a product of politics than the realities of the past. These attempts to homogenize history has often led to an absence of the contribution made by individuals and organizations who appear discordant to the stereotypes that are often politically normalized. The Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind and its leader, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani, appear in the history of Northeast India as one such case. In the midst of communal contests and nationalist assertions fraught with conflicts of loyalists versus betrayers, the story of the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind and its struggle and sacrifice in the making of independent India is often ignored or is ‘absent’ in history writing. This essay seeks to address this gap in research.

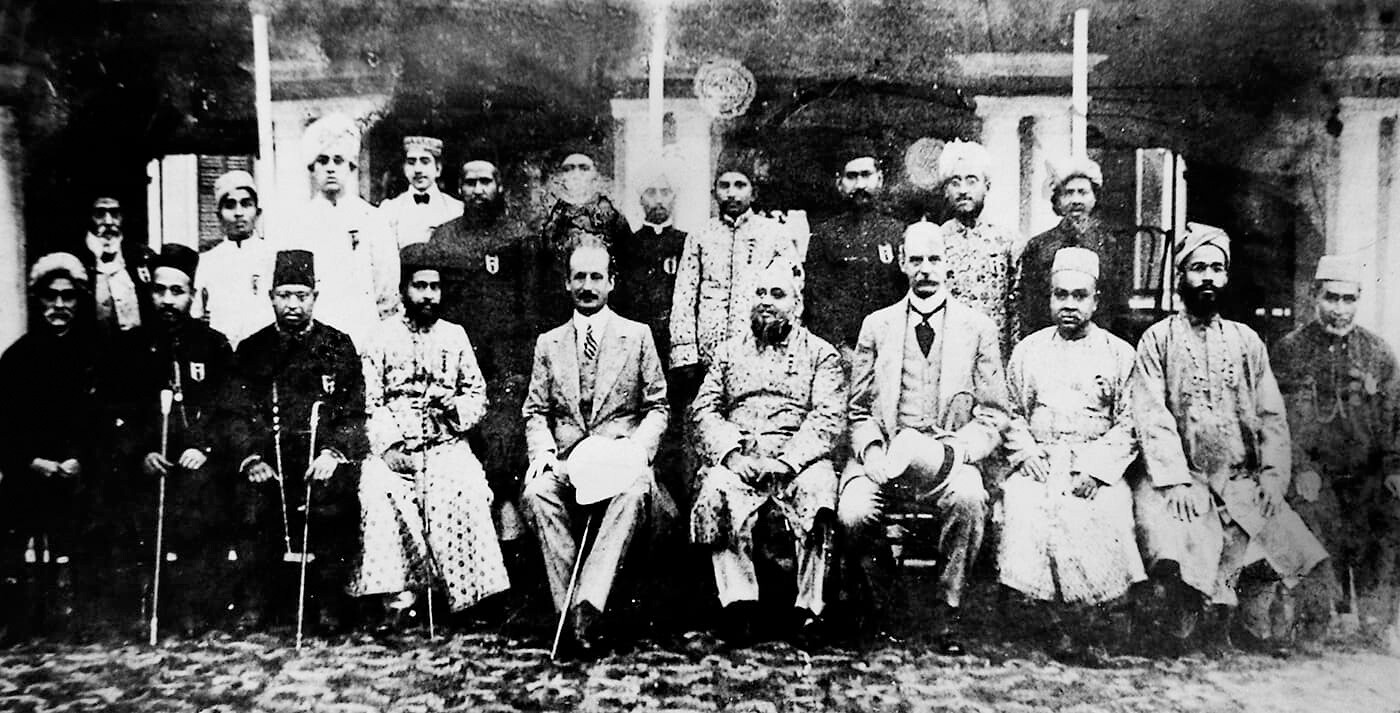

The founding members of the All India Muslim League at the baradari of Shah Bagh in Dhaka, December 30, 1906. Wikimedia Commons.

In the midst of a nationalist discourse fraught with conflicts of loyalists versus betrayers, the story of the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind and its leader, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani, a Sufi from Deoband related to the Chisti-Sabiri order are outstanding for their struggle and sacrifice in the making of independent India. Perhaps, in an age where history is as much a theatrical contest both for ‘ideas’ and ‘participations’ in politics, it is worthwhile to remember ‘fragments’ within the Muslim community which relentlessly struggled against the dominant grain to make a place for themselves in the Indian nationalist narrative and against partition. When the government pronounced on June 3rd 1947, to decolonize along with the partition of Assam, they also decided to hold a referendum at Sylhet. While it set the ball rolling for the formal partition of the subcontinent it also brought the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind, one of the most prominent Ulama organizations into a confrontation with the Muslim League, the principal proponent of Pakistan. The ‘Pakistan’ plan was not only against the nationalist goal of a plural unified sub-continental polity of India championed by the Congress, it was also against the idea of a ‘composite nationalism’ championed by the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind and its leader, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani.

Therefore, when Sylhet went into the motion for a referendum in the run-up to the partition of the subcontinent, the Jamiat and the Muslim League found themselves on opposite sides. For colonial Assam, especially the district of Sylhet, it was a difficult but a unique situation. Nowhere in the subcontinent except in Sylhet, was the partition question limited to a district only and in the process, Assam was made the third theatre of sub-continental partition. That apart, in no other situation, a referendum was used to either elicit public opinion or to demarcate boundaries of India and Pakistan. Assam was the only Indian colonial state which was a non-Muslim province and yet had to experience partition and become a playground of the League versus Congress competitive politics.

The Sylhet Referendum was the final showdown of political might between the Congress-Jamiat combine on the one hand and the Muslim League on the other, culminating in a vicious political campaign steeped in religious symbolism and rhetoric. Open campaigns asking the Muslims to vote for Pakistan because it was an Islamic dream state[1] was matched by the Congress openly soliciting the assistance of the Deobandi and other Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind preachers to campaign against the League. With the referendum becoming acrimonious, the rhetoric of the elections of 1946 in favour of and against Pakistan were liberally revived and invoked.

When Lord Mountbatten went to London to workout a formal partition proposal and the June 3rd 1947 Declaration was made, the campaign for the referendum started in true earnest. While the then premier of Assam welcomed the proposed plan and looked at the transfer of Sylhet as a fait accompli,[2] on the ground the situation was marked by struggles and contests from competing sides, each launching an earnest do or die campaign. For the League, having lost the possibility of incorporating the entire province of Assam into East Pakistan, they spared no effort to ensure the transfer of this Muslim majority district of south Assam into Pakistan. Abdsus Subhan, the Chairman of the League Sylhet Referendum Campaign Committee was categorical in Calcutta when he asserted that:

“At this critical stage of the struggle of our national liberation, all the rank and file must unite forgiving and forgetting the past.”[3]

Keeping this objective in mind, a committee to oversee the campaign and ensure its success was created in Calcutta, as Bengal was the nerve centre of the League campaign in the East. The significance of the campaign and its religious content was outlined by Mohammad Abdul Subhan himself, as he asserted that, “…the first and the last battle of Pakistan will be fought in Sylhet. The whole Muslim world is looking towards us…” Statements and assertions as the ones indicated above made it clear to participants and observers alike that Sylhet was now a symbol of Muslim pride and victory if the referendum was to be a victory for Islamic identity and solidarity.

It is this religious fervour which drew the League volunteers to this district from far and wide for the campaign was a religious duty, with volunteers coming from provinces from as far as Bihar and Punjab.[4] The entire campaign was characterised by much tension. Despite their confidence of victory, the League left no stone unturned in their high-pitched campaign led by their Ulama from the front. It is this campaign that brought these Muslim divines to the forefront of the League political programmes and campaigns and again into a confrontation with the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind. The referendum campaign saw these divines on either side, playing their political role with intense passion.

Abdus Subhans statement, that, the Muslims “cannot sign their death warrant. We must win or we should perish”[5] brought the desperate situation out into the open for the Muslim League. That the campaign was transferred into a religious conflict was evident from the fact that the name of religion and God were liberally invoked to emphasise and bring about Islamic solidarity, a phenomenon which was rarely achieved in earlier or in any other League campaign.

“Our cause is noble & Allah will be with us. On July 6th and 7th, we are to give our verdict whether we want national liberation or perpetual slavery. Our destiny lies in our hands. I hope God will help us. Ameen.”[6]

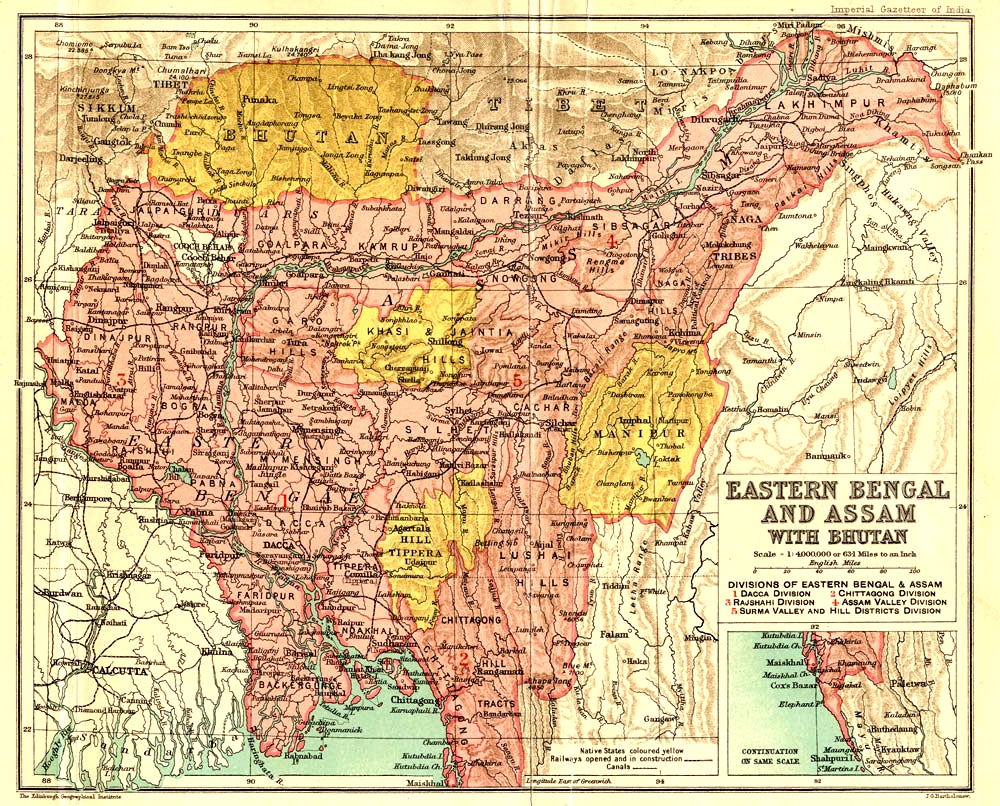

The Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam, Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1907. Wikimedia Commons.

People like Maulana Akram Khan and Maulana Abdul Huq, the Pir Sahib of Fufura addressed thousands of people. The Cachar unit of the Muslim League also formed a sub- committee with Maulvi Nasib Ali Masumdar as President to campaign in the referendum. Several batches of volunteers were dispatched to Beani Bazar, Bhanugas, Karimganj and Badarpur to undertake an intensive campaign and a great deal of enthusiasm was generated in these areas amongst Muslims. It was no mean achievement in the task of mobilisation, that about 15,000 League volunteers were engaged in the League campaign at Sylhet.[7] There was no doubt about the Islamic character of the League campaign because their gatherings were always accompanied with the presence of religious leaders. When the League supporters gathered at the Sylhet Dargah Sharif on the 8th of July 1947, it was marked by the participation of a large number of Ulama from different parts of India. On the occasion of Shab-e-Barat, it was addressed by Alems such as Maulana Jafar Ahmad Osmani and Sahebzada Pir Sarhina, and the issue discussed was undoubtedly the Sylhet Referendum. Prayers were offered for the success of the League campaign in the Referendum.[8] The religious content of the League campaign was not only seen in the speeches that were delivered at League meetings but also in the posters that were circulated within the district, before the Referendum. Muslim voters were asked to prove their identity as pucca Muslims, by casting their vote in favour of Pakistan.[9] This was corroborated by the description of the content of another poster that was pasted at the Beani Bazar market by the League:

“Congresser Taka

Musalmaner Iman”[10]

The Muslim League’s emphasis was undoubtedly on the arousal of religious passion as is shown by a song that was often sung by them to emphasise the religious persecution that was faced and likely to be faced in a Hindu majority Assam:

“Asamer Julumer Katha

Jibon Thakte Bhulbo na

Ammra to bhai Assame Thakbona

…

Haati diya Masjid Bhanglo

Gombujer Chin raklo na,

Aaamra to Bhai Assame thak bo na”[11]

The last two lines are a clear indication towards the attempt of the League to emphasise the religious deprivation of Muslims in a Hindu state, which was the overwhelming nature of their vicious propaganda. Pakistan was flaunted as the ethereal goal for the Muslims of the subcontinent and Sylhet joining it was glorified as the climax of this movement. Therefore, in League rhetoric, joining Pakistan should be the aim of every Muslim in the district. This campaign did not always tread on formal patterns of political campaigns, for, the campaign for Pakistan and Sylhet joining it was launched by the local preachers at the remote villages. Where the formal League campaigners could not visit, these preachers or Maulvis became the self-styled League volunteers and leaders to carry forward the League’s perspective on the referendum. This was important because many areas of Sylhet, especially Sunamganj was rendered inaccessible during the rainy season when the Referendum was organised. The Maulvis served as League volunteers in these areas taking advantage of the position, they held in a traditional rural Muslim society. While as preceptors, guides and advisors to the local people in the rural areas, they traditionally played a role in the local society, and could easily mould the political views of their coreligionist followers as well.[12] The religious nature of society was such, that, the rural Muslims were fully enmeshed in orthodoxy and ritualistic rigour through a sustained campaign of Islamisation. This gave the Maulvis scope to organise a sustained campaign within the structured confines of the local mosques, and to draw a consistent group of followers that could ensure the penetration of the League message in the daily sermons, and Friday prayers became increasingly a long affair with these mosques becoming the nerve centres of the Referendum campaign. Besides these modes, the Maulvis would also address the people on the days of ‘haat’ or market and their speeches equated a vote for joining Pakistan with a great service to Islam.[13] Muslim League supporters therefore whole heartedly participated in this struggle in which even at the close of the campaign, a last ditch attempt was made to mobilise the people through slogans of religion.[14] Therefore, the League was successful in building among the rural masses, the belief that by voting for Pakistan and in favour of Sylhet joining it they would be supporting a “religious cause”.[15] With the overtly religious slogan of ‘Allah ho Akbar’ renting the air, the feeling was carnivalesque, in casting their vote in favour of a Muslim homeland, they were expressing their Islamic solidarity and strengthening the Islamic fraternity.[16]

This campaign based on Islamic solidarity and religion was not limited to the League alone. The Congress leadership in Sylhet extensively used the preachers of the Jamiat-ul Ulama-i-Hind who descended on Sylhet to campaign for its retention with Assam and as part of the Indian Union. The Jamiat presence ensured a favourable impression for the Congress amongst Muslims in their past political campaigns. Jamiati Alems were used even during the 1946 elections in Assam. The Ulama campaigned for the Congress in numerous Muslim predominant areas.[17] These divines of the Jamiat-ul Ulama-i-Hind even joined the fray during the Sylhet Referendum. Unfortunately, the Jamiat in their own way also unconsciously contributed to strengthen Islamic solidarity. Their opposition to the Muslim League with regard to Pakistan was rooted in their theological interpretation to the Islamic concept of statehood as against the League’s effort at achieving an Islamic state within the western ideological and political framework. Therefore, while on one hand they believed in Muslims belonging to a separate ‘millat’ “which refers to a collectivity with a Sharia,”[18] they were on the other hand opposed to Pakistan because they did not believe in the creation of a separate state or nation on lines of western political thought and believed that Indian Muslims were part of a worldwide Islamic religious fraternity “under the jurisdiction of a Khalifa.”[19] By this rhetoric, their campaign against Sylhet joining Pakistan only contributed in strengthening Islamic identity and solidarity and the Pakistan Movement of the League. In fact, the campaign of the Jamiat, for this reason alone, though extensive bore no fruit. The Jamiat contingent led by the likes of Maulana Mufti Nayeem, Secretary of the All India Jamiat-al-Ulama-i-Hind or Maulana Shahid Mian Fakhri, President of the united province Jamiat-al-Ulama-i-Hind thus could not build up an intelligible differentia between themselves and the League before the Muslim masses, when they campaigned in Sylhet district. The Sylhet district leadership of the Jamiat could not withstand the sustained campaign of the League, which was much better organised than their opponents.[20]

The Muslim League identified the Jamiatis as their principal adversaries. The Jamiats worked closely with the Congress and preached syncretic messages. Their slogan, along with their partners, the Congress was:

“O people of Sylhet

Do not make the land of Chaitanya and Shah Jalal

A part of Pakistan”[21]

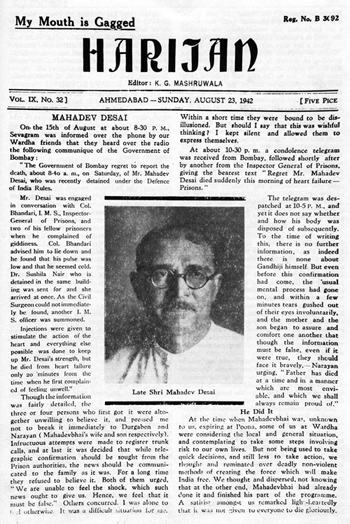

Harijan, 23rd August 1942, Wikimedia Commons.

The Muslim polity in Sylhet was a divided house between the League and Jamiat-al-Ulama-i-Hind. The League vilified the Jamiat and hurled indignities on them. It was reported that they even tortured the Jamiatis where they got an opportunity. Writing in the Harijan dated 27th July 1947, Gandhi rued:

“The plight of the Nationalist Muslims is sad…They have come under the shadow of suspicion.”[22]

The Referendum proved beyond any doubt that the Muslim polity in Eastern India was sharply divided on political and ideological lines, contrary to the claims of the League about the existence of a Muslim monolithic identity. The League launched an all-out war against their intra-community adversary. Intelligence reports noted with concern that the League was pulling out all stops to crush the Jamiati challenge. An intelligence report filed for Sylhet and Cachar noted, that, “In Karimganj, lists of Jamiats have been made out for use of persuasion or force for conversion to the Muslim League creed.”[23] Intimidation made it difficult for the Jamiati workers to campaign against the League at Sylhet. Leaders of the Jamiat in a statement pointed out that:

“Hooliganism and rowdyism created by some people on Sylhet had made it impossible for Nationalist Muslim workers to move freely.”[24]

The League devoted special attention to those areas which were traditional Jamiat pockets of support, and also launched a movement to convert Jamiat workers in Jaintia Pargana to the League point of view. Threats of molestation and aggressive campaigning were used by the League to achieve their purpose.[25] Often, the League ridiculed the Jamiatis in public meetings. The League spared no effort to paint their coreligionist rivals as traitors of the faith; often equating them with Hindus, who in Muslim League rhetoric were idolators.

“…If you have joined their ranks

why don’t you start worshiping Idol…”[26]

was one such song sung by the Leaguers to vilify the Jamiatis. The strength of the League campaign was such that it could easily overcome its opponents and coercively absorb them into its creed, which the Dawn dated the 4th July 1947 brought out with much clarity, with the caption:[27]

“Assam Jamiat Leaders Join League”

A procession taken out in Sylhet town, a day before the voting was to commence in the Sylhet Referendum carried a poster which read:

“League and the Jamiat have become one

Pakistan has been realised”[28]

The League by July 1947 had shattered all opposition to Pakistan from all quarters. Both the Congress and the Jamiat were crushed under the onslaught of the League campaign built on the idea of Pakistan and Islamic solidarity. The idea that rang clearly in the League rally at Badarpur, when the League and the converted Jamiati leaders addressed the meeting on the 4th of July 1947 was that:

“The choice was now between Kufristan and Islamistan”[29]

Finally, when the people of Sylhet went to vote on the 6th and 7th of July 1947, the die was already cast and polarisation of the communities almost complete. The impact of this campaign carried on by the League on even the Jamiat members only helped to reinforce Islamic solidarity in Sylhet Muslims.

Though the result of the Referendum being in favour of the district joining Pakistan in that sense did not come in as a surprise to most leaders in the Congress and League alike, there is no doubt that the Referendum marked the crescendo of a sustained campaign to crystalise the Islamic identity of the Muslims of Sylhet, on the one hand, and the Muslim League victory over the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind on the other. It was in more ways than one a naked display of the crafty utilization of brutal force in a modern political setup which culminated in the partition of not only the sub-continent but also the state of Assam. While the League victory left the Congress solitary and against their wish as only spokespersons for the Hindus, as Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan said, “The Muslim League has demonstrated that the Congress can only speak for the Hindus,”[30] alongside it left the Jamiatis shattered and decimated.

The campaign at Sylhet left little doubt that the Muslim League which started as an organisation to safeguard Muslim interests had come of age as the principal representative of Muslim political articulation and representation, alongside it also showed that all Muslims of the sub-continent were a divided house on the question of partition and Pakistan. Though the League had left the Jamiat-al-Ulama-i-Hind far behind in this race, the ‘nationalist Muslims’ had also made their mark as one of the principal breakers against the tide of Pakistan, despite their defeat. This left the Jamiatis precarious and vulnerable in the new political situation. While Sylhet had come to symbolise, at least for the common league volunteer, the battle of life and faith, the Jamiatis were the ‘gaddar’ and ‘gomraha’ Muslims. For the nationalist narrative, the Jamiat-ul-Ulama-i-Hind were as much co-sharers of the vision of unified India as the Congress. This is something which we seem to overlook in most historical narratives across the sub-continent and which requires an immediate corrective as we move into celebrating seventy-five years of independence and partition.

Notes and References

- Pakistan Vs Kafristan – Poster of the League at the 1946 election, Packet. No. 144, APCC Papers, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NNML), New Delhi. ↑

- G. Bordoloi quoted in Dawn, 10th June, 1947, NMML. ↑

- Abdus Subhan, quoted in Star of India, 4th July, 1947, NMML. ↑

- S. Paul Choudhury, ‘Sylhet Referendum,’ Unpublished M.Phil. Dissertation, Department of History, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong, 1947, p.50. ↑

- Star of India, 4th July, 1947, NMML. ↑

- Ibid., 4th July, 1947, NMML. ↑

- Ibid., 8th July, 1947, NMML. ↑

- Ibid., 8th July 1947, NMML ↑

- Bidyut Chakraborty, ‘The Hut and the ‘Axe’, The 1947 Sylhet Referendum, IESHR, Vol. XXXIX, 4 (2002). ↑

- The author’s interface with Shri S. Das who was a student in Beani Bazar, Panchakanda Pargana, Sylhet. ↑

- The author’s interface with Shri M. C. Das who was a student in Sunamganj, Sylhet. ↑

- B. Dutta, ‘Ulama in Politics,’ Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of History, North-Eastern Hill University, Chapter 2, 2005. ↑

- B. Chakraborty, Pearsons Report to Stork the Referendum Commissioner, op.cit. p.339. ↑

- Ananda Bazar Patrika, 3rd July, 1947, quoted in B. Dutta, ‘Ulama in Politics,’ op.cit. p.242. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Packet No. 144, APCC Papers, NMML. ↑

- P. Hardy, ‘Muslims in British India,’ Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1972, p. 244. ↑

- Ibid., p.195 ↑

- Pvt. Secy. to Viceroy papers, Annexure C of the Referendum Report, National Archives of India (NAI), p.2. ↑

- The author’s interface with Late P.K. Hore, resident of Laban, Shillong, 5th May, 2007. ↑

- Harijan, NAI. ↑

- File 17, Abstract of Intelligence year 1947, Assam State Archives. ↑

- B. Dutta, Religion in Politics, Pilgrims Publishers, Varanasi, Kathmandu, p. 207. ↑

- File 17, Abstract of Intelligence, 1947, Assam State Archives. ↑

- The author’s interface with Late P.K. Hore, resident of Laban, Shillong, 6th,August, 2006. ↑

- Dawn Microfilm, NMML. ↑

- The author’s interface with Sri R.K. Bhattacharjee, at Shillong, 8th August, 2008. Translations by the author. ↑

- Dawn, 4th July, 1947, NMML. ↑

- Dawn, 11th January, 1946, NMML. ↑

Binayak Dutta is Co-founder and Editorial Chair at Partition Studies Quarterly. He teaches Modern India in the Department of History, North Eastern Hill University, Shillong. His areas of special interest include Partition of India studies, Migration, Displacement and Gender Studies. He has authored three books besides research papers in edited volumes and journals. He is editing an upcoming volume on Partition in northeast India.