Abanindranath Tagore, Bharat Mata, Watercolour, 1905. (Wikimedia Commons).

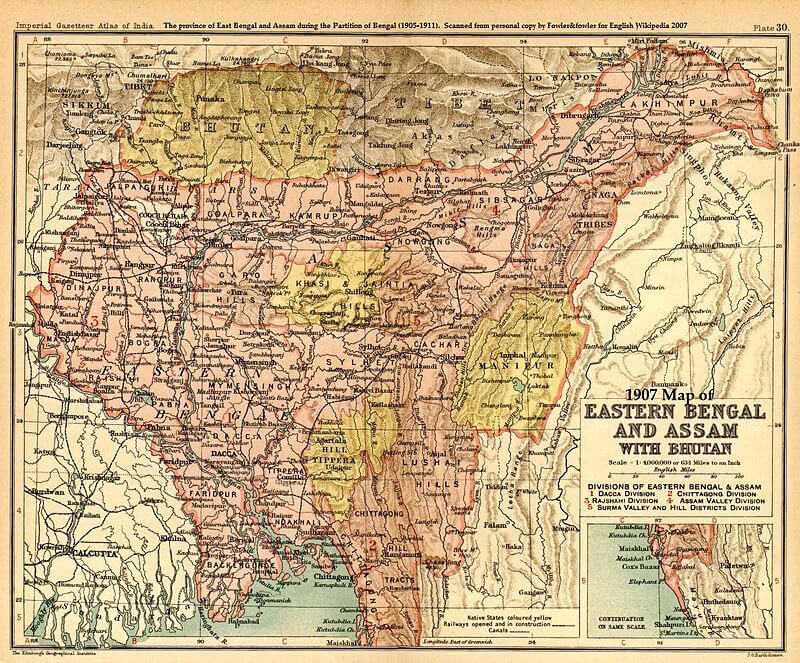

In the last quarter of the 19th century, nationalist aspirations and the ideology of motherhood intertwined with religious, cultural and aesthetic domains – a politicization quite unique in colonial Indian history.[1] With the positioning of one’s selfhood and identity in opposition to western rule, ‘motherhood’ emerged as a domain which colonized subjects could claim as their own.[2] In 1905, Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951) painted the ‘Bharat Mata’, and it was in this same year that Viceroy Nathaniel Curzon applied imperial cartography for the reorganization of the northeastern regions of British India. Eastern Bengal and Assam or the Meghna-Brahmaputra river basin became one administrative province (with Dhaka as the capital), and this partition led to the division of the Muslim peasantry majority in eastern Bengal from the Hindu land-owning professionals in western Bengal. The resistance from Assam to this reorganization was both in linguistic and cultural terms, within the politics of economic expansion of British India (into the northeast) with Calcutta as its capital.

The swadeshi movement has its roots in the anti-partition struggle and was formally proclaimed with the Boycott Resolution in August 1905 in the Calcutta Town Hall. The launch of swaraj (self-rule) and swadeshi (self-economy) stands on the axis of modern territorial politics of South Asia. Taking this moment of an expanding nationalism in colonial Bengal which established an enduring ‘spatial frame for Indian national thought,’[3] this essay investigates the aesthetics and politics of ‘Bharat Mata’ (1905) and its ‘investiture in motherhood.’[4] The prevalence of the mother cult in Bengal in both its great and little traditions[5] offers us an insight into the mythography of motherhood as does the sanction derived from the religious practices of worshipping the Devi of Hindu Bengal.[6] It aided in ‘Hinduising’ the tone of Indian nationalism, while offering a counter-point to male (Occident) imperialism.[7] Alongside, one must note that the Muslim League was formed in 1906 in Dhaka to safeguard the rights of Indian Muslims.

Given the above, what might be the relation between nationalism, painting and the modernist project, and what might be the ‘colour of swadeshi?’ Colonial art education and British academic realism caused a wave of reactions in the Indian artistic sphere. In colonial Bengal, two clear phases of art production can be identified, firstly, the Westernizing period (1850-1900) of the absorption of Renaissance naturalism;[8] secondly, the cultural nationalist turn (1900-1922) led by the bhadralok class and Orientalist groups of Bengal.[9] “The concept of India, or (in Sanskrit) Bharat, as a bounded organic national space became the template onto which swadeshi programs were projected.”[10] Tied to this were literary/performative renditions of the Unabimsa Purana (1866) by Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay (first published anonymously), K.C. Bandhopadhyay’s play Bharat Mata (1873) and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhya’s novel Ananda Math (1880).[11]

The Modern Review – Inner Page. First published in 1907. (Wikimedia Commons).

Abanindranath Tagore rose to prominence in the early decades of the 20th century “largely through the dual promotion and patronage of British Orientalist and Indian nationalist interests,”[12] exemplifying a national style, and tied to the discipline of Indian art history.[13] Ramanananda Chatterjee’s Prabasi (in Bengali) and The Modern Review (in English) reproduced his paintings alongside the nationalist and aesthetic discourses of three prominent Orientalists: E. B. Havell, Ananda Coomaraswamy, and Sister Nivedita.[14] In particular, Chatterjee’s Picture Albums, a series of bound plates in full colour[15] was highly influential in the cultural politics of that time. While each of them had their own stances, these three Orientalists idealized the Hindu and Buddhist past and sought to frame the Bengal School paintings on a non-naturalist spiritual register.[16] Orientalist research on Indian art traditions, inevitably established the binary of ‘Western’ (material) and ‘Eastern’ (spiritual) art,[17] with the Bengal School style emerging around 1900.

In his formative years, Abanindranath was tutored by European painters and his shift to find an ‘Indian-style’ art language is traced to the year 1897 and to two artistic encounters: firstly, a set of Irish melodies illuminated and gifted by the painter Frances Martidale, and secondly, a set of Indian miniatures, specifically in the late-Mughal style of a provincial Mughal school from the late 19th century, gifted by his brother-in law.[18] These two types of miniature manuscripts offered an aesthetic alternative to European oil painting (the by-product of colonial opium trade) alongside the tutelage of E.B. Havell who offered Abanindranath to study his collection of Mughal and Pahari miniatures. In 1902, the Japanese art historian and philosopher of pan-Asianism, Kazuko Okakura visited the Tagore household in Jorasanko, Calcutta, transporting a direct influence of Japanese aesthetics on Abanindranath.[19] In 1903, Okakura sent two young Japanese painters, Yokoyama Taikan and Shunso Hishida, to Calcutta to further an intercultural exchange of aesthetic procedures.

Abanindranath Tagore. (Wikimedia Commons).

In the pursuit of common aesthetic interests with Japonisme, Abanindranath further developed his own ‘wash’ techniques after watching Yokoyama Taikan occasionally go over his paintings with a large brush dipped in water to soften the forms.[20] Abanindranath applied as many as fifteen transparent colour washes on Whatman English cartridge paper, allowing the paper to dry, and then ‘bathing’ the painting in a basin of water to achieve the misty luminosity (which he referred as moro-tai)[21] that is characteristic of his oeuvre. He used methods of fresco bueno, tempera, and a mixing of European and vernacular pigments to complete his works.[22] It is worthwhile to contextualize that Japan had defeated Russia in 1905 and “as such provided Bengal (then in the grip of partition rioting) with an ideological resource with which to fight British imperialism.”[23]

Bharat Mata (1905) was painted by Abanindranath around the pinnacle of the swadeshi movement, with the Bengal School style representing a break from the prevailing norms of western academic naturalism, and implying alternate spiritual standards of aesthetics.[24] “In this, the claims of national authenticity were made for its art and it was appropriated by the Indian nationalist struggle for liberation from British rule.”[25] The art historian, R. Sivakumar examines this painting succinctly:

“The young and full-bodied, four-armed ascetic figure holding a sheaf, cloth, palm leaf manuscript and prayer beads in her hands was read as a nationalist mother-goddess bestowing the blessings of food, clothing, learning and spiritual strength on her children. Considering that the issues that stoked the Swadeshi movement included dissatisfaction with the agrarian, manufactural, educational and political policies of the colonial government, and that the segments of the society that the activists sought to bring together under the banner of Swadeshi included landowners, traders, students, and the intelligentsia, the iconography is self-explanatory.”[26]

The techniques that Abanindranath applied to his paintings (discussed above) accentuated the luminous ethereal quality that we see in Bharat Mata with a halo, who stands in a field of soft emotive colour (bhava), with a faint suggestion of land and white lotuses at her feet. There is no contoured map binding this figure unlike later popular representations of the ‘motherland’ in India, that visually fixated the connection between cartography and the geo-body. Abanindranath’s mother-image is a familiar ascetic Bengali woman with bangles, sindoor, and beads in the image of Shri, the goddess of prosperity;[27] a personalized affectionate ‘mother’ that made the impersonal concept of the ‘nation’ more graspable for nationalist revolutionaries to appropriate this transcendental image in the politics of heroism.[28]

This appropriation of the ‘Hindu’ visual form of the mother-image becomes significant when contextualized with Bankim’s poem Vande Mataram (Hail, The Mother) that became the hymn for Bengali revolutionary extremism.[29] Abanindranath’s iconic Bharat Mata was utilized in a political rally in 1905, enlarged by a Japanese artist and passed in fundraising swadeshi processions, and the rhetoric surrounding it shaped much of its significance.[30] Sister Nivedita wrote about this painting two years later in The Modern Review in an article titled, “The Function of Art in Shaping Nationality,”[31] and held it in exclusive regard for its contribution to nationalist ideals. Given this ‘Hindu’ tone of Indian nationalism in colonial Bengal, it has been argued that this would “leave the Muslim alienated and disenfranchised […] leading inexorably to communal confrontation and national fragmentation.”[32]

The Province of East Bengal and Assam during the Partition of Bengal (1905-1911), Imperial Gazetteer Atlas of India, 1907. (Wikimedia Commons).

If Abanindranath’s Bharat Mata became a central icon in the polemical construct of nationality, it was because of the turn of political and cultural forces of his time. “As a matter of fact, the art of Abanindranath Tagore was a selective engagement with modernity through strategic and performative choices based on modern constructions of an “Indian classicism,” a pan-Asianism of Japanese origin and a regional and local cultural history.”[33] Originally, as the historian Sugata Bose notes, “the iconic creations of both Bankim and Abanindranath invoked Banga Mata (Mother Bengal) and not Bharat Mata (Mother India),” as being representative of a unified regional linguistic community[34] of eastern and western Bengal. It served a local and regional cultural consciousness and “prior to the appearance of nationalized communal politics was one in which the image of the Mother goddess had a strong emotional charge to Hindu and Muslim alike.”[35] The Muslim poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam’s poems often invoked the mother goddess imagery,[36] and the liberation struggle of Bangladesh “revived the entire turn-of-the-century corpus of patriotic Bengali songs, including the large number of those visioning the region as the Mother.”[37]

One could expand the reading of Abanindranath’s Bharat Mata to his pluralistic conceptual and aesthetic choices in the construction of his artistic oeuvre. Ranging from influences of Mughal and Pahari miniatures (particularly its linearity), Japanese ‘wash’ techniques, and free use of European and vernacular pigments for an ‘Indian’ style, Abanindranath exercised a subjective sensibility to shape a ‘critical alternate modernism,’[38] that goes beyond essentialized Orientalist aims. While responding to the ‘spirit’ of a swadeshi cultural assertion of his time in the Jorasanko household and regional locale, Abanindranath’s practice involved an ‘aesthetic securalization’[39] that responded to heterodox sources and identities. “In fact, although Bharat Mata is considered the most nationalist or political or swadeshi painting not only of Abanindranath’s but of the period, it was actually modelled after something very personal: the face of his daughter.”[40]

It would be worthwhile to dwell here on how Banga Mata/Bharat Mata was co-opted within the regional context of the 1905 partition which conflated spatial conflict and economic inequity in India. It was both an expansion of imperial space and the establishment of a “distinctively Indian national space that emerged for the first time between 1870-1914 inside Britain’s imperial globalization.”[41] If Muslims in East Bengal welcomed this partition as a way to secure economic opportunities, the elite bhadraloks in West Bengal filed petitions against this severance expressing a disregard for wider inclusiveness. Separating the latter from the “progressive, flourishing, and cultured districts of Dhaka and Mymensingh, along with the Chittagong districts”[42] and annexation to a ‘backward/underdeveloped province like Assam’ defied commonsense for them.[43] Moreover, these elite petitioners felt that the two Bengals shared a common linguistic and cultural heritage[44] and the land beyond the river Meghna was one of ‘wild aboriginal races,’[45] thereby claiming a ‘national homeland’ that alienated Assam.[46] Thus, the metaphors of Banga Mata/BharatMata appropriated by bhadralok nationalists delineated an exclusive spatial territory within the politics of imperial capitalism, “where British India overlapped classical Bharat in the Gangetic lowlands”[47]

If the “swadeshi movement confronted British imperial privilege, it also valorized a united Bengal, positioning Calcutta over Dhaka,”[48] and isolating colonial Assam and its centres of Shillong and Guwahati.[49] In 1911, Assam again became a Chief Commissioner’s province and east and west Bengal were reunited; the unfolding of territorial politics into the events of 1947, and later the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war is deeply rooted in the spatial inequalities and the political interests of 1905. The territorial longing of a united Bengal still inflects academic and cultural discourse,[50] and Assam’s claim for its own ‘motherland’ through the Assam Movement (1979-1985) has had a lasting impact on the shaping of contemporary regional politics. The various ethno-nationalisms that erupted in northeast India after 1947 has its roots in an antipathy towards an ‘Indic’ identity and Indian national space. The migrations that the partition perpetuated keep border anxieties with Bangladesh alive, and the rhetoric of ‘settlers’ or ‘outsiders’ has given rise to the complicated combination of NRC-CAA in northeast India. With the current regime’s attempts at ‘Hinduising’ democracy and altering the concept of citizenship, Bharat Mata stands at crossroads in the 21st century, amidst the fault-lines of identities and a blinkered nationalism.

Notes and References

- Jasodhara Bagchi, Representing Nationalism: Ideology of Motherhood in Colonial Bengal, Economic and Political Weekly, October 20-27, 1990. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- David Ludden, Spatial Inequity and National Territory: Remapping 1905 in Bengal and Assam, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 46, No.3, May, 2012. ↑

- Jasodhara Bagchi, Representing Nationalism: Ideology of Motherhood in Colonial Bengal, Economic and Political Weekly, October 20-27, 1990. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Partha Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1850-1922: Occidental Orientations, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Natasha Eaton, “Swadeshi” Colour: Artistic Production and Indian Nationalism, ca. 1905-ca.1947, The Art Bulletin, Vol.95, No. 4, December 2013. ↑

- Sadan Jha, A History of Bharat Mata and Why We Need to Draw a Parallel with the National Anthem, The Indian Express, March 18, 2006. ↑

- Debashish Banerjee, The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore, Sage Publications, 2010. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia, University of North Carolina Press, 2010. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Natasha Eaton, “Swadeshi” Colour: Artistic Production and Indian Nationalism, ca. 1905-ca.1947, The Art Bulletin, Vol.95, No. 4, December 2013. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Natasha Eaton, “Swadeshi” Colour: Artistic Production and Indian Nationalism, ca. 1905-ca.1947, The Art Bulletin, Vol.95, No. 4, December 2013. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Debashish Banerjee, The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore, Sage Publications, 2010. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Jasodhara Bagchi, Representing Nationalism: Ideology of Motherhood in Colonial Bengal, Economic and Political Weekly, October 20-27, 1990. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Debashish Banerjee, The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore, Sage Publications, 2010. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Debashish Banerjee, The Alternate Nation of Abanindranath Tagore, Sage Publications, 2010. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Jasmin Cohen, Nationalism and Painting in Colonial Bengal, SIT Digital Collections, Fall 2012. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- David Ludden, Spatial Inequity and National Territory: Remapping 1905 in Bengal and Assam, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 46, No.3, May, 2012. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

Amrita Gupta is Co-founder and Executive Editor at Partition Studies Quarterly. An art historian and writer, she is involved in art education, archiving and cultural management. With roots in Shillong and a research interest in the visual culture of northeast India, she has documented its art history with a focus on Assam. Her art writings have been published in edited books, journals and websites. She is program director at Mohile Parikh Center, Mumbai, with curatorial interests in socially engaged art and creative placemaking.