On the Emergence of Modern Linguistic and Territorial Boundaries in Northeast India with Focus on Assam

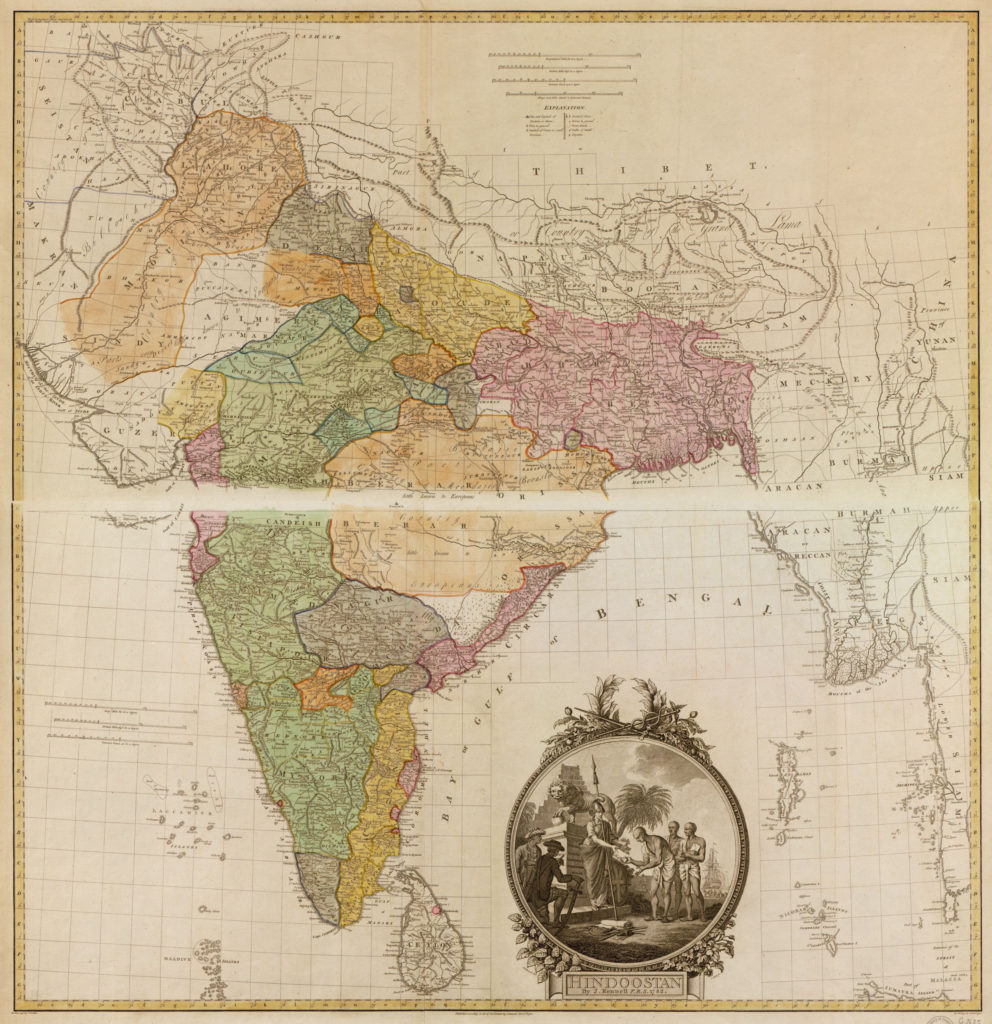

James Rennell, Map of Hindoostan, 1782. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Northeast India in History

The region that is now called Northeast India only came into existence in 1947 with the drawing of the current borders of India. Before that, until the colonial period, it was part of a shape-shifting space with Tibet and Bhutan to the north, Burma to the east and Bengal to the west and south. Within this region there existed three ancient valley kingdoms, in what are now Assam, Manipur, and Tripura, and numerous tribal chieftainships in the hills. The largest of these kingdoms, and the oldest in the historical record, was the kingdom of Kamrup in the valley of the river Brahmaputra in what is now Assam.

The earliest material evidence that has so far been found from this ancient kingdom are a set of copper plates called the Nidhanpur plates, after the place in Sylhet in modern Bangladesh where they were found, and the written records of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Hiuen Tsang. Both date to the 7th Century A.D. and the reign in Kamrup of a monarch named Kumar Bhaskarvarman. The Nidhanpur copper plates describe a long genealogy of over 3,000 years by which the descent of Bhaskarvarman is ascribed to a mythical king named Naraka, known from ancient Hindu texts called Puranas, whose son Bhagadatta finds mention in the epic Mahabharata for his battle against the hero Arjun. The plates, inscribed in Sanskrit, and replete with homages to Hindu gods and the king Bhaskarvarman, concludes by making a grant of land to a group of Brahmins.[1]

Hiuen Tsang, who visited Kamrup in 643 A.D., left a fuller description of the kingdom and its people. According to him, “The country of Kamarupa is about 10,000 li (nearly 1,700 miles) in circuit. The capital town is about 30 li. The land lies low, but is rich and regularly cultivated…”[2]

The country was bounded to its east by a line of hills, the Chinese pilgrim noted. “The frontiers are contiguous to the barbarians of the south-west of China”. On the other side of a two-month journey across mountains and rivers through the lands of the barbarians, according to him, lay Szechuen. On the south-east were forests with numerous herds of wild elephants, and 1,200 li beyond, the kingdom of Samatata, corresponding to East Bengal. Hiuen Tsang made the journey from the university of Nalanda in today’s Bihar where he was then studying Buddhist law. He described going 900 li (around 150 miles) east from Pundra Vardhana, a kingdom in the area corresponding to today’s West Bengal and northern Bangladesh, and crossing the “great river” to arrive in Kamrup. The “great river” was either the Karatoya, or the Brahmaputra. The location of the kingdom’s capital remains uncertain to this day.

“The men are of small stature and their complexion a dark yellow. Their language differs a little from that of mid-India”, Tsang wrote. “They adore and sacrifice to the Devas and have no faith in Buddha”. The King Bhaskarvarman, according to Hiuen Tsang, was a Brahman, and his family had been ruling the kingdom for 1,000 generations. These observations on religion match the evidence from the Nidhanpur copper plates. However, what was the ethnicity of these people of “dark yellow” complexion? And what was this language that differed “a little from the language of mid-India?” It was not Sanskrit; that was the language of scholarship and scriptures.

The linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji, in his masterwork on the Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, wrote of Hiuen Tsang’s account, “it is curious to find that, according to him, the language of the Kama-rupa people ‘differed a little’ from that of Mid-India. Hiuen Thsang is silent about the language of Pundravardhana or Karna-suvarna: it can be presumed that the language of these tracts was identical with that of Magadha, which was the ‘Midland’ or ‘Central India’ or ‘Mid-India of the Chinese traveller. Now, one would expect an identical language to have been current in North Central Bengal (Pundra-Vardhana) and North Bengal and Western Assam (Kama-rupa) in the 7th Century, since these tracts, and other parts of Bengal, had almost the same speech, at least in morphology, in the 15th and 16th Centuries, as can be seen from the extant remains in Bengali and Assamese.” Chatterji surmises that “perhaps this ‘differing a little’…refers to those modifications of Aryan sounds which now characterise Assamese as well as North and East Bengali dialects” [3].

The common language, with its “little” differences, from Magadha to Kamrup, corresponding to today’s Bihar, Bengal and Assam, at the time was, according to Chatterji, a form of Magadhi Apabhransa. Oriya, the language of Orissa, too, is a part of this group. Chatterji characterises the period from the 8th-11th Century as one in which the language was in a formative, fluid stage, and “the specifically Bengali, Maithili, and Oriya characteristics were in all probability manifesting themselves but were not yet fully established”. The Bengali group of dialects, according to him, came to be united by a common literary language based on West Bengali which became fully established by the 15th century. “The common dialect current in North Bengal and Assam continued as one speech, as a member of the Bengali-Assamese group of dialects. In the 15th century, it split up into two sections, Assamese and North Bengali, when Assamese started on a literary career and an independent existence of its own by not acknowledging the domination of literary Bengali, already established in East Bengal as well”.

What emerges quite clearly from this is the absence of modern linguistic identities at any time before the 15th century. Although linguistic identities such as Bengali and Assamese are today held almost universally to be somehow primordial, the languages themselves are far from primordial. They are, in historical terms, of fairly recent origin – and it is evident that the corresponding identities could not predate the languages.

The ancient kingdom of Kamrup, which existed in Hiuen Tsang’s time, and stretched from the frontiers of China to north Bengal, began to go into decline shortly after his visit. The king Kumar Bhaskarvarman died without leaving an heir. Two dynasties, the Mleccha and the Pala, followed, but by 1100 A.D. these too had ended. In 1198 A.D, Muhammad Bakhtiyar Khilji invaded what remained of Kamrup from neighbouring Bengal, where he had established himself as king. He was the first Muslim ruler of Bengal. His invasion of Kamrupa, which he passed through on his way to attempt a conquest of Tibet, however ended in disaster. He had easy passage on his way to Tibet but his army came to grief on its way back when the king of Kamrupa besieged and defeated him. Most of his followers were drowned in trying to cross a river, probably the Brahmaputra, and only Khilji himself with a few hundred horsemen succeeded in reaching the other bank. [4] Another Muslim invasion of the remains of the Kamrup kingdom occurred in 1227 and a third in 1278. Both ended in defeat, and in the latter case, the Sultan Tughril Khan himself was killed. In 1337, Muhammad Shah, according to Gait, “sent 100,000 horsemen well equipped to Assam, but the whole army perished in that land of witchcraft and not a trace of it was left”. The use of the word “Assam” is however anachronistic; the territory of that name only came into existence much later, through the efforts of a dynasty called the Ahom.

This dynasty, which came to shape the destiny of modern Assam, was established by a group of men from the Shan hills of Myanmar and adjacent areas in what is now Yunnan province in China. A prince named Sukapha had migrated from there through the jungles and hills with a band of followers, said to number 9,000 men, in the early 1200s. The little army reached what is now Upper Assam around 1228 A.D. They married into the local tribal communities, such as the Barahi, which was eventually integrated into an Ahom identity. Other local groups such as the Motoks and the Morans were given positions in the new administration. The Kachari, Khampti, and Miri tribes were similarly included. By and by, all major local ethnic groups were included in the Ahom administration. The kingdom initially was restricted in area to a small territory in upper Assam close to what is now Sibsagar. Ahom chronicles called Buranjis narrate a long record of wars with neighbouring kingdoms such as the Chutiya and Kachari, and battles with tribes such as the Nagas, that lasted for the next three centuries. The original language of these Buranjis was the Tai language of the Shan kings. The kings also followed their own religion. The first Ahom king to adopt a Sanskrit title was Suhungmung, who ruled from 1497-1539. He adopted the title of Swargadeo, meaning “lord of the heavens”. During his reign Buranjis began to be written in Assamese. The king, however, did not formally adopt Hinduism. The first Ahom monarch to become Hindu was Chao Hpa Hso-Tam La who became Jayadhvaj Singha. He ruled from 1648-63.[5]

The Ahom territory, even at the beginning of Jayadhvaj Singha’s reign, was restricted to what is now called upper Assam, which is the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra valley. The lower Brahmaputra valley, known as lower Assam, was at the time in the possession of the Mughal governors of Bengal and the Koch kings, heirs to what remained of Kamrup. In 1658, Shah Jahan, the Mughal emperor in Delhi, fell ill. A battle of succession broke out between his sons. Taking advantage of this situation, Pran Narayan, the king of Koch Bihar, which corresponds to today’s Cooch Bihar in north Bengal, raided Goalpara in lower Assam. Jayadhvaj Singha also assembled a strong army and attacked Gauhati. “On arriving, he found that the Faujdar had fled without waiting to be attacked”, writes Gait. The Ahoms, elated by their easy victory, then marched against the Koch army and drove them across the Sankosh river. “They thus became masters of the whole of the Brahmaputra valley”.

Their mastery did not last long unchallenged. After the Mughal war of succession ended with the coronation of Aurangzeb, the new emperor despatched his Bengal governor, a man from Isfahan in Persia named Mir Jumla, to retake his lost possessions. The army was accompanied by a fleet of boats sailing up the Brahmaputra, commanded primarily by European officers, mainly Portuguese, according to Gait. Mir Jumla’s forces defeated the Ahoms in a series of battles. Jayadhvaj Singha fled to Namrup, the easternmost province of his kingdom, accompanied by a number of his nobles. On 17th March 1662, Mir Jumla entered the Ahom capital, Garhgaon, and occupied Jayadhvaj Singha’s palace. However, his victory too was short lived. The monsoon rains came and the rivers flooded. The Ahoms began a guerrilla resistance. Diseases broke out. “Fever and dysentery became terribly prevalent, and a detachment that numbered fifteen hundred men at the beginning of the engagement was reduced to five hundred; many horses also died [6]”. At the end of September, the rains ceased, and the Mughals again gained the advantage, but here had been a famine in Bengal and further supplies were not forthcoming. Moreover, Mir Jumla himself fell ill, and could only travel by palanquin. The Mughals therefore accepted the Ahom king’s offer of peace. A treaty was concluded by which Jayadhvaj Singha agreed to send one of his daughters to the imperial harem – she was converted to Islam, given the name Rahmat Banu Begum, and married to Aurangzeb’s son Muhammad Azam Shah – give twenty thousand tolas of gold, six times that amount of silver, and forty elephants, and cede land west of the Bharali and Kallang rivers to the Mughals. Mir Jumla died of his illness on his way back to Dhaka and was buried in the Garo Hills of Meghalaya.

However, the issue of unpaid war indemnities led to a second series of hostilities between the Ahoms and the Mughals. The new Ahom king, and his able general Lachit Borphukan, successfully retook Gauhati. Aurangzeb sent a Mughal force under a Rajput, Raja Ram Singh, but this time, the Ahoms prevailed in a series of engagements of which the final one was a famous naval victory on the Brahmaputra at the Battle of Saraighat in 1671. This again made them masters of the Brahmaputra valley, but again, the mastery did not last long, as a war of succession now broke out in the Ahom kingdom and the Nawab of Bengal was able to retake Guwahati in 1679. The new Ahom king Gadadhar Singha, on assuming the throne in 1681, once again fought and won back control of Gauhati. After this the city which is now the capital of Assam remained with the Ahoms until the advent of colonial rule. What is now western Assam, comprising the districts of Goalpara and Dhubri, were however still parts of Bengal. When the East India Company, after defeating the Mughal emperor Shah Alam in the Battle of Buxar in 1765, became the ruler of Bengal, it came into possession of Goalpara. Assam passed into Burmese hands when the Burmese invaded and over-ran the Brahmaputra valley thrice between 1817 and 1822. The Ahom kingdom was annexed to the Burmese kingdom, and the Ahom king Chandrakant Singha fled to Bengal. This brought the Burmese and British into conflict, and led to the British victory over the Burma kingdom in first Anglo-Burmese War of 1824-26. That brought the Ahom and Manipur kingdoms of what is now Northeast India into East India Company rule following the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826.

The western frontiers of the current state of Assam including its border with Bangladesh came to be fixed as matters of administrative convenience during the years of colonial rule. Goalpara and Dhubri became parts of Assam in 1874 as part of an ongoing reorganisation of the administrative areas under Bengal, which at the time included most of today’s Bihar, Jharkhand, coastal Orissa, all of Bangladesh and West Bengal, Assam, and parts of Arunachal Pradesh. This was a vast and diverse area and the colonial rulers, who had brought with them modern ideas of identities and territories, set about rearranging it according to the technologies and worldviews of their times.

Map, Printing Press and Census

Northeast India and its surroundings

The long history of the areas that now comprise Assam reveal a living process of shifting languages, identities and borders. This was true of the wider region of Northeast India as a whole. The areas that currently lie at the disputed frontier with China, for instance, were areas that remained off the map until the early 1900s. The southern frontier, between Meghalaya and what is now Bangladesh, which has Sylhet on the Bangladesh side and the Khasi Hills on the other for part of its length, crystallised earlier. The historian David Ludden dates it to 1790 and describes it as the culmination of a period of geographical change that involved “the interaction of five very old, dynamic, and overlapping geographies – of nature, land use, markets, culture and governance – which had together defined Sylhet historically as a region with indefinite boundaries and shifting substance”[7]

Definiteness of boundaries only began to occur with the advent of the East India Company. The first detailed map of India, titled “Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan” by Major James Rennell, was published in 1782. If India itself had any indigenous history of map-making, no example of note has survived. All known maps from antiquity that depict India are from Western sources. The earliest of these, which was not a drawn map but a written description of geographical locations, was in the Geography of Claudius Ptolemy who lived from 90-168 A.D. The earliest surviving Greek edition of the Geography to contain drawn maps is from the 13th century. Indeed, Ptolemy and his maps remained virtually forgotten until a slow revival of his knowledge that began with the Moroccan scholar Al-sharif al-Idrisi’s map made for the Sicilian king Roger, and later famous as The Book of Roger, in 1154. Al-Idrisi’s map was inscribed in Arabic and oriented with south at the top. The problem of accurately projecting a spherical world on a two-dimensional plane had not yet been solved in his time. That would have to await the arrival of Gerard Mercator and his world map of 1569. “Within his lifetime, Mercator’s projection was a qualified failure. Sales were slow, and many…complained that Mercator’s inability to explain his methods made them virtually useless for practical use for seaborne navigation. It took an Englishman, Edward Wright, in a series of mathematical tables in his book Certaine Errors in Navigation (1599) to provide the calculations required to translate the projection for the use of pilots, who slowly began to adopt the method during the course of the seventeenth century” [8].

By then competition for the acquisition of colonies and trade routes were well established among the kingdoms of Western Europe. The process had started with the event that kicked off the beginning of political map-making on a global scale – the audacious division of the world into two halves between the Portuguese and Spanish Castilian crowns by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, with all lands east of a line 370 leagues due west of the Cape Verde islands going to Portugal and everything to the west going to Spain.

When the East India Company arrived in India, its directors realised the need for maps. Major Rennell, before his famous map of India, was commissioned to draw maps of India’s navigable rivers. In 1765, according to a paper by John Ardussi on “The Quest for the Brahmaputra River and its Course According to Tibetan Sources”, Rennell made an expedition to trace the course of the river “from Goalpara in Bengal to the frontier of Assam, a distance…of twenty-two miles by river”. In his preface to his Memoir of Hindoostan, Rennell wrote, “Whatever charges may be imputable to the Managers of the Company, the neglect of useful Science, however, is not among the number. The employing of Geographers, and surveying Pilots in India; and the providing of astronomical instruments, and the holding out of instruments to such as should use them indicate, at least, a spirit above the mere consideration of Gain”.

The process of exploration and map-making that began with Rennell continued throughout the years of British colonial rule in India. All of India’s current political borders were drawn by the British Raj. In Northeast India, a whole new worldview was imported to create modern identities and borders in the years of colonial rule. The first element of this new worldview was that of linguistic identity. This occurred as a result of the standardisation of vernaculars and their rise to literary status, a process that occurred in Europe in the early 1800s and was carried to India soon after. Until then, around the world, there had been scholarly and literary languages that differed from the local vernaculars. In Europe, Latin was the language of the Roman Catholic Church and the universities, and also served as an official language in countries where a multitude of tongues were spoken [9]. In India, Sanskrit had enjoyed a similar status as the language of the scriptures and the pundits. Literacy was restricted to Brahmin boys and the notion of universal literacy, and that it might serve any useful purpose, would then have been considered absurd. Books in any case were relatively rare and expensive objects; the printing press was still a rarity.

The first book printed in the Assamese language, as was the case with many other languages, was the Bible, which was published under the name “Dharma pustak” meaning “book of dharma” in 1813. The first newspaper in Assamese, Orunodoi, was published by the American Baptist Mission press in Sibsagar from 1846. This led to the elevation of the Sibsagar dialect to the status of standard Assamese – a decisive turn in history, because until then, the dialects of lower Assam, corresponding to ancient Kamrup, had been the dominant language of culture in the area. The greatest poet-saints of medieval Assam, whose influence is strong in its cultural life to this day, were the Vaishnava gurus Sankardeb and Madhavdeb, both of whom lived and worked in lower Assam and Cooch Behar and composed their hymns in Brajabuli, a literary form of Maithili. According to the Assamese linguist Upendranath Goswami, “Up to the seventeenth century, as the centres of art, literature and culture were confined within western Assam and the poets and writers hailed from this part, the language of this part also acquired prestige”[10]. The collapse of the Koch kingdoms of western Assam and the ascendancy of the Ahom kingdom shifted the centre of political power to the area around the Ahom capitals near Sibsagar in upper Assam. The subsequent arrival of the missionary press, and its publication of the first books and newspapers in the Sibsagar dialect, were therefore crucial in the creation of standard Assamese and the Assamese linguistic identity.

The proliferation of the printed press and the ability to print standardised images and text cheaply had revolutionary impact. The process, described as print-capitalism by Benedict Anderson in his influential book Imagined Communities, enabled the creation not only of new linguistic identities but also of new imaginations of territories. Throughout history, maps, which required efforts of years to draw, had been the luxuries of kings. Now it became possible for every official and every merchant to possess one. The nation-state could not have been invented without this artefact. Its existence depends on the shared imagination of a territory among its inhabitants. This imagination was created through the official map, which created an image that was otherwise inaccessible to the average individual. Anderson wrote of the two final avatars of the map, both instituted by the late colonial state, which directly prefigured the official nationalisms of twentieth century Southeast Asia. The first of these was the appearance, late in the nineteenth century especially, of ‘historical maps’ that were “designed to demonstrate, in the new cartographic discourse, the antiquity of specific, tightly bounded territorial units. Through chronologically arranged sequences of such maps, a sort of political-biographical narrative of the realm came into being, sometimes with vast historical depth. In turn, this narrative was adopted, if often adapted, by the nation-states which, in the twentieth century, became the colonial states’ legatees”. The second avatar was of the map as logo. “Its origins were reasonably innocent – the practice of imperial states of colouring their colonies on maps with an imperial dye…in the final form all explanatory glosses could be summarily removed: lines of longitude and latitude, place names, signs for rivers, seas, and mountains, neighbours. Pure sign, no longer compass to the world…instantly recognisable, everywhere visible, the logo map penetrated deep into the popular imagination, forming a powerful emblem for the anticolonial nationalisms being born.[11]”

The map was accompanied by the census. The first census of Assam to try and enumerate the entire population was conducted in 1871. It was a fitting of people into imagined boxes of religion, language, and caste. The categories for religion were Hindoos, Mahomedans, Sikh, Buddhists and Jains, Others, and “Religion not known” which had 425,175 persons. “Although nearly the whole of the inhabitants of British India can be classed under one or other of the two prevailing religions”, Henry Waterfield wrote in his Memorandum on the Census of British India published in 1875, “it will be found that when arranged according to nationality or language, they present a very much greater variety”. This “greater variety” that the colonial official eye noticed was however one that simplified people into species. “Bengal proper, and some of the adjacent districts, are inhabited by the Bengali, living amid a network of rivers and morasses, nourished on a watery rice diet, looking weak and puny, but able to bear much exposure, timid and slothful, but sharp-witted, industrious, and fond of sedentary employment; the Bengali-speaking people number some 37 million. Allied to them, both in language and descent, even more conservative, bigoted, and priest-ridden, are the Ooryas, or people of Orissa, numbering four million. The Assamese, of whom there are less than two million, speak a language very similar to Bengali, but have a large mixture of Indo-Chinese blood; they are proud and indolent, and addicted to the use of opium.”

The fitting of the population into caste categories produced certain oddities. For instance, the heading of “Hindoos and persons of Hindoo origins” included 10 million Brahmins and 5 million Kshatriyas and Rajputs, but the single largest category by far was “other castes” with 105 million. There were also 8 million who were either outcastes or didn’t recognise caste, 786,311 who didn’t specify caste, and 595,815 “native Christians” – who were enumerated as “Hindoos or persons of Hindoo origins”. It would appear that the Western idea of caste, which was imported into India from the Spanish and Portuguese caste systems – the word itself comes from the Spanish/Portuguese “casta” meaning race – was mapped on to a complex pre-existing Indian reality that had certain resemblances, but also a great many differences, from the Western. The same was true of religion; the word “dharma”, a concept of moral philosophy, was mistranslated as religion, with pernicious after-effects. The 1871 census also categorized castes by occupation, which is how it used to operate in Indian society across religions, and graded them as “superior”, “intermediate”, “trading”, “pastoral” and so on. Some curious categories were invented or discovered. “Dancer, musician, beggar and vagabond” was a single category with 72,247 individuals in Bengal and Assam. The writer notes that “Mr Beverley, however, says that the number of separate tribes and castes which have been found to exist in Bengal does not probably fall short of a thousand, while, if their subdivisions and septs or clans were taken into account, they would amount to many thousands”. In other words, a teeming diversity was being flattened into a nation of timid, slothful but sharp-witted people.

Education was not yet a proper category in the census enumeration in all provinces. In Bengal, the information was not sought except in a few municipal towns. “Seeing how imperfect the statistics must be, it is not worthwhile to analyse them minutely; but it may be observed that, in the nine provinces for which returns have been made, there are, among the 123 millions of people inhabiting them, only 4 millions who are returned as being able to read and write, or as being under instruction”, Waterfield wrote. The construction of the self-image of Bengalis, Assamese, Hindus and Muslims, in the manner they had been imagined by their colonial masters would have to wait until a larger section of the population was duly taught to see themselves as they were seen. It was a worldview that would be communicated and internalised, first by the elites, and then, gradually, through diffusion, by the masses.

The Nation’s Onward March

India’s idea of itself as a nation owes much to the West. The Indian National Congress, which was the party of India’s struggle for independence, was founded by a retired British civil servant, Allan Octavian Hume, in 1885. Almost every single one of the leading lights of the movement at the time of independence, from Mohandas Gandhi to Mohammad Ali Jinnah to Subhas Chandra Bose to Jawaharlal Nehru to Bhimrao Ambedkar were educated in the West. They were all, in their own ways, nationalists.

It would be rare to find critiques of nationalism from among the colonised people in those days of freedom struggles. There was one. The writer Rabindranath Tagore, whose songs eventually provided the national anthems of two countries, India and Bangladesh, had spoken and written on the subject. In his essay on “Nationalism in the West” published in 1921, he wrote, “The world-flood has swept over our country, new elements have been introduced, and wider adjustments are waiting to be made. We feel this all the more, because the teaching and example of the West have entirely run counter to what we think was given to India to accomplish. In the West the national machinery of commerce and politics turns out neatly compressed bales of humanity which have their use and high market value; but they are bound in iron hoops, labelled and separated off with scientific care and precision. Obviously, God made man to be human; but this modern product has such marvellous square-cut finish, savouring of gigantic manufacture, that the Creator will find it difficult to recognise it as a thing of spirit and a creature made in His own divine image”.

Tagore was against what he called the “colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism” and the “fierce self-idolatry of nation-worship”. He considered “government by Nation” to be “neither British nor anything else; it is an applied science and therefore more or less similar in its principles wherever it is used…before the Nation came to rule over us, we had other governments which were foreign, and these, like all governments, had some element of the machine in them. But the difference between them and the government by the Nation is like the difference between the hand loom and the power loom”.

His was a lone voice in the wilderness. Today almost 100 years later, the entire intellectual debate in the world is a dogfight between acolytes of colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism and fierce self-idolators of nationalisms. The world itself is organised as nations and the largest club of these nations, the United Nations, enshrines the rights of peoples – doubtless constituted through similarities of language, religion and ethnicity – to self-determination.

The independence of India did not end the rise of what is called national consciousness among its peoples. In Northeast India, there have been major armed insurgencies seeking independent nation-states in Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura, and smaller ones in the remaining two provinces in the region, Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh. There is no tribe or ethnic group of any size that has not seen a militant movement for nationhood. Nowhere was the nation imagined in any way other than ethno-linguistic. For instance, in Assam, the United Liberation Front of Asom, which led the armed fight for independence from India, based its claims on the Assamese being an ethnolinguistic people with a distinct national identity and territory who could not cohabit in the same country with their more populous neighbours. The group also killed Hindi-speaking migrants in targeted attacks. Broader efforts to define the territory in ethno-linguistic terms have been carried out under the benign eyes of various governments over the decades. The most popular and recurrent of these is the effort to weed out the Bengali speakers, Muslim and Hindu, who are seen as rightfully belonging in West Bengal or Bangladesh. The question, asked directly or indirectly, of every Bengali in Northeast India is “why are you here”.

This is a question that is now being asked by the machinery of the nation itself, through the process of the National Register of Citizens. This national register for the ‘nation’ of Assam is intended to exclude all those who cannot prove citizenship, either of themselves or their parents and grandparents, before March 24, 1971, a date agreed upon in an accord called the Assam Accord that was signed at the end of an agitation against illegal migration into Assam in the early 1980s. The Assam agitation against illegal migrants saw several instances of rioting of which the most memorable was the Nellie massacre of 1983 in which more than 2,200 men, women and children were killed overnight for being Bengali Muslims. Similar riots against those seen as outsiders occurred in other provinces of the region as well. In Meghalaya’s capital of Shillong, speakers of the Bengali and Nepali languages, regardless of religion, have been targets of ethnic cleansing from 1979 onwards [12].

The current Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party government in India is trying to turn this ethnolinguistic nationalism into a subset of religious nationalism. It has supported drawing up the National Register of Citizens for the whole country, and pitched it as a device to identify and eventually deport illegal Bangladeshi migrants and Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar. However, the NRC in Assam has left out 1.9 million people, of whom around two-thirds are said to be Hindus, mainly Bengalis; official statistics on this is not available. In order to convince its Hindu voters that they will not be deported if they are found to lack the specified documents from close to 50 years ago, the BJP has proposed to amend the country’s citizenship law to enable easy citizenship for non-Muslims from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. This has led to a resurgence of both linguistic and religious identity politics in Assam, and in the Northeast in general, with strong opposition emerging from various parties and groups in the Northeast. Tribal groups, Assamese jatiyotabadis, Hindu and Muslim Bengalis, and the region’s Gorkha community are all insecure and agitated by the combination of NRC and Citizenship Bill. Apart from Bengal and Punjab, the only other province of British India to experience Partition was colonial Assam, which saw the district of Sylhet going to East Pakistan in a controversial referendum held in 1947. The sharpening of both religious and linguistic divides therefore does not augur well for the region which has a history of ethnic riots and insurgencies.

State of Conflict

The long survey of history in Assam from the 7th Century to now reveals a process by which modern languages emerged, attained literary status, and eventually became fixed through the advent of print which enabled books and newspapers to be published in large numbers at affordable prices. The rise of modern linguistic identities coincided with the rise of maps and censuses and notions of counting, measuring and classification as the correct scientific ways of organising knowledge of peoples and places. It was the time when revolutionary ideas in the scientific world were gaining currency. The animal and plant worlds were being organised according to the principles of taxonomy established by Carolus Linnaeus in 1737. The elements were being placed neatly into the periodic table. The world was being explored, surveyed and mapped, and enormous new “discoveries” – such as Mount Everest – were being made. Order was being brought to chaos…or so it seemed.

The human world did not escape the ideas of scientific classification on an industrial scale, being classified into nations on the basis of language, religion and ethnicity. Race had always existed but racism now became scientific and precise. The Roman empire had black and brown emperors, such as Septimius Severus and Caracalla, and Indian emperors and kings came from a wide range of castes and creeds until medieval times. Several of the ancient and medieval kings were known for their cruelty, but in the new world of nations, cruelty also became neat and well organised. The first industrial genocide, of the Jews in Nazi Germany, was carried out with scientific efficiency. The American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki too were achievements of rational, scientific nationalism. The genocide of the Cultural Revolution in Mao Zedong’s China was scientific.

The distance to which a state core could exert power was restricted in earlier times by limitations of communications technologies. The absence of roads and mechanised transport made travel, especially in the mountains, extremely difficult. Large parts of the world remained non-state spaces. Northeast India and its adjacent parts of Southeast Asia, especially northern Myanmar which it borders, had large tracts of these non-state spaces. Technological advances that led to the death of distance have come alongside ideas of nation-states, enabling them to stretch out and occupy spaces. The notion of national sovereignty and neatly demarcated borders has proved thorny in South Asia because states are trying to claim spaces for themselves that, in some places, were never state-spaces. The troubled boundaries between India and China, and between Pakistan and Afghanistan, are two examples.

On a broader scale, the experiences of India and its northeast see echoes elsewhere. The push for nationhood based on ideas of shared ethnic and linguistic identities is seen in Scotland in the United Kingdom and Catalonia in Spain. These may be viewed as examples of an incomplete process of nation-formation stretching towards completion. After all, if a language and a shared history make a people, and the people have the right to self-determination in a territory that they own, there is nothing theoretically wrong with such claims. Even the British vote for Brexit and the renewal of nationalisms elsewhere in Europe are entirely in line with theories of what the nation-state is. A nation-state with a history is supposed to belong to a people, such as the English people, and to be sovereign. Majoritarianism exists in the very DNA of the nation-state.

The contrary push towards “globalisation” is primarily economic in character. Whether as the European Union or China’s Belt and Roads initiative, it is geared towards connectivity for purposes of trade and commerce. Money is a powerful force, and so are the communication technologies of our times. Where little nationalisms run counter to the imperatives of trade and communication they may eventually fail. However democratic politics works by mobilising groups. Populists around the world, from Narendra Modi in India to Donald Trump in America, have found that they can mobilise groups using identity politics that imagines the nation as predominantly Hindu or White. Without recognising the fluidity of human identities – which censuses froze into rigidity in the 19th century and the surveillance state aims to freeze further – it would appear that we are in for a clash between little and big nationalisms in the first instance, and between big nationalisms themselves at a later stage. The fact that the modern world of nations was born out of the first and second World Wars is perhaps not an accident of history, but an essential feature of the nature of a world order, now rendered outdated by communication technologies and growing global environmental concerns, of competing nation-states that ultimately require nationalism to justify their existence.

Notes and References

- Translation by Padmantha Bhattacharya Vidyavinoda, Epigraphia Indica, Vol XII, edited by E.Hultzsch ↑

- A History of Assam, Edward Gait ↑

- The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, Suniti Kumar Chatterji ↑

- A History of Assam, Edward Gait ↑

- Tai-Ahom Religion and Customs, Padmeswar Gogoi ↑

- A History of Assam, Edward Gait ↑

- The First Boundary of Bangladesh on Sylhet’s Northern Frontiers, David Ludden, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh ↑

- A History of the World in Twelve Maps, Jerry Brotton ↑

- Barricades and Borders: Europe 1800-1914, Robert Gildea ↑

- A Study on Kamrupi: A Dialect of Assamese, Upendranath Goswami ↑

- Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Benedict Anderson ↑

- Insider/Outsider: Belonging and Unbelonging in North-East India, Edited by Preeti Gill and Samrat ↑

Samrat Choudhury is Co-founder and Executive Editor at Partition Studies Quarterly. A journalist and author from Shillong, his writings have appeared in Granta, The Hindustan Times, The Times of India, India Today, Outlook, The Indian Express, The New York Times, The Friday Times of Pakistan, and the Dhaka Tribune in Bangladesh, among others. He is the author of one novel and several short stories, many of which have been translated to other languages.